The Romantic Period in English literature (commonly dated 1798–1837) marks a decisive transformation in literary sensibility. Its hallmark is the elevation of imagination, feeling, nature, and individual subjectivity over the Neoclassical emphasis on reason, decorum, and public norms. Romantic writers reconfigured poetic form and language, revived interest in folk and medieval modes, explored aesthetic concepts of the sublime and the picturesque, and reacted—sometimes enthusiastically, sometimes with disillusionment—to seismic historical events such as the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and the social effects of the Industrial Revolution.

This chapter gives a sustained, advanced-level account of the period: precise chronology of major events and their literary impacts; subdivisions and generational groupings; categorical lists of major authors and works; extended summaries of core works; thematic and stylistic analysis; critical approaches; and suggestions for primary and secondary reading.

I. Major historical events (1798–1837) and their literary impacts

Romantic literature did not arise in a vacuum. The political, economic, scientific, and cultural upheavals of the era shaped authors’ subjects, forms, and public roles.

1. The French Revolution (1789) and its aftermath

Impact on literature:

- The French Revolution initially inspired many British intellectuals and writers (Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley)—an enthusiasm for liberty, fraternity, and social reform.

- As the Revolution radicalized (1792–1794) and the Reign of Terror followed, many writers moved from hope to disillusionment or caution. This political disillusionment fuels the Romantic tension between revolutionary idealism and tragic skepticism (Shelley’s later radicalism vs Wordsworth’s conservative turn).

- Political engagement also led to repression in Britain: trials for sedition, surveillance, and censorship made political poetry and pamphleteering both urgent and dangerous.

2. The Rise and Fall of Napoleon (1793–1815)

Impact:

- Napoleonic wars produce both a prolonged period of conflict (affecting trade, travel, and social order) and a strange cultural ambivalence: admiration for a heroic figure fused with horror at the scale of warfare. Byron’s and Shelley’s political attitudes and the aura of exile around many Romantics reflect this climate.

- Victory at Waterloo (1815) inaugurates an era of conservative reaction across Europe.

3. The Industrial Revolution (late 18th–early 19th c.)

Impact:

- Rapid mechanization, urbanization, factory labor, and new class formations (industrial bourgeoisie, working poor) provoked Romantic critiques of dehumanization and the loss of connection to nature. Blake, Wordsworth, and Coleridge frequently register the anxieties of enclosures, child labor, and mechanized work.

- Conversely, industrial growth expanded print, literacy, and book markets—so Romantics reached larger audiences via periodicals, reviews, and circulating libraries.

4. Enclosures, Rural Displacement, and Social Protests

Impact:

- Rural dispossession and economic hardship appear in Romantic poetry as elegy for disappearing rural life and as ethical provocation (e.g., Wordsworth’s pastoral laments, the social themes in Southey’s and Clare’s poems).

- Popular protests (Luddite disturbances c. 1811–1816) and repressive responses (the Six Acts 1819) underscore the social tensions many Romantics narrate or mourn.

5. Peterloo Massacre (1819), the Six Acts (1819), and Political Repression

Impact:

- The killing of protestors at Peterloo (Manchester) and subsequent government repression radicalized some writers and hardened others’ pessimism about reform prospects. Shelley’s The Masque of Anarchy (composed 1819, published later) responds directly to Peterloo.

6. Catholic Emancipation (1829) and Reform (1832)

Impact:

- The period culminates in partial political reform (Catholic Emancipation 1829; Reform Act 1832) signaling shifting political structures and the slow incorporation of popular demands into parliamentary politics—changes that the late Romantics witnessed but whose full social consequences unfold after 1837.

7. Advances in the Natural Sciences and Antiquarianism

Impact:

- Developments in geology, optics, and natural history (Darwin’s later work comes after our period) change how writers think about time, deep time, and humanity’s place in nature.

- Romantic antiquarianism and medieval revival (Walter Scott’s novels and influence on the Gothic revival) recover premodern forms and national pasts.

II. Subdivisions, generations, and periodization

Romanticism is usefully subdivided both by chronology and by “generations” of writers. This helps track shifts in tone, politics, and formal experiment.

A. Pre-Romantic antecedents (late 18th century)

Writers like William Blake (Songs of Innocence 1789; Songs of Experience 1794), Robert Burns (poetry from the 1780s), Charlotte Smith (Elegiac Sonnets 1784), Thomas Gray (earlier) and Cowper form a background: they emphasize feeling, the local voice, and a turn to nature that prefigures Romantic priorities.

B. First Generation / Early Romantics (1798–1807)

Key markers: Publication of Lyrical Ballads (1798), Wordsworth and Coleridge’s manifesto (Wordsworth’s Preface to Lyrical Ballads, expanded 1800 and 1802).

Principal figures: William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, (William Blake often grouped as precursor/continuing voice).

Characteristics: Ballad forms, language of the common man, focus on perception, nature as teacher, subjectivity and memory. Political radicalism initially present in many.

C. Middle / High Romanticism (c. 1807–1818)

Changes: Wordsworth’s maturation, Coleridge’s intense theoretical work, and the rise of the second generation. The Napoleonic wars continue; forms diversify.

New figures rising later in this span: Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Keats (active slightly later).

Characteristics: Larger ambitions (epic fragments, longer autobiographical poems), refined lyric forms, increased myth and classical reference.

D. Second Generation (c. 1812–1821)

Principal figures: Byron (Childe Harold 1812–), Shelley, Keats (active especially c. 1817–1821).

Characteristics: Daring lyric experiment, political radicalism (Shelley), Byronic hero and exile, intense sensuous lyricism (Keats). Often more cosmopolitan and theatrical than the first generation. Many died young (Keats 1821; Shelley 1822), sharpening Romantic myth.

E. Late/Transition period (1815–1837)

Key features: A literary field widened by historical novels (Walter Scott), the consolidation of the novel as central (Jane Austen — contemporaneous with some Romantics), religious revivals, and growing marketization of literature. Political reforms begin to take effect. Romantic aesthetics diffuse and mutate into Victorian forms. Poets such as John Clare and later Felicia Hemans, Letitia Elizabeth Landon (L.E.L.) add different voices (peasant lyric, women’s lyric).

III. Major genres and representative authors (categorical)

Below are principal literary genres with major authors and representative works listed in each category.

1. Lyric and Narrative Poetry (central to Romantic genius)

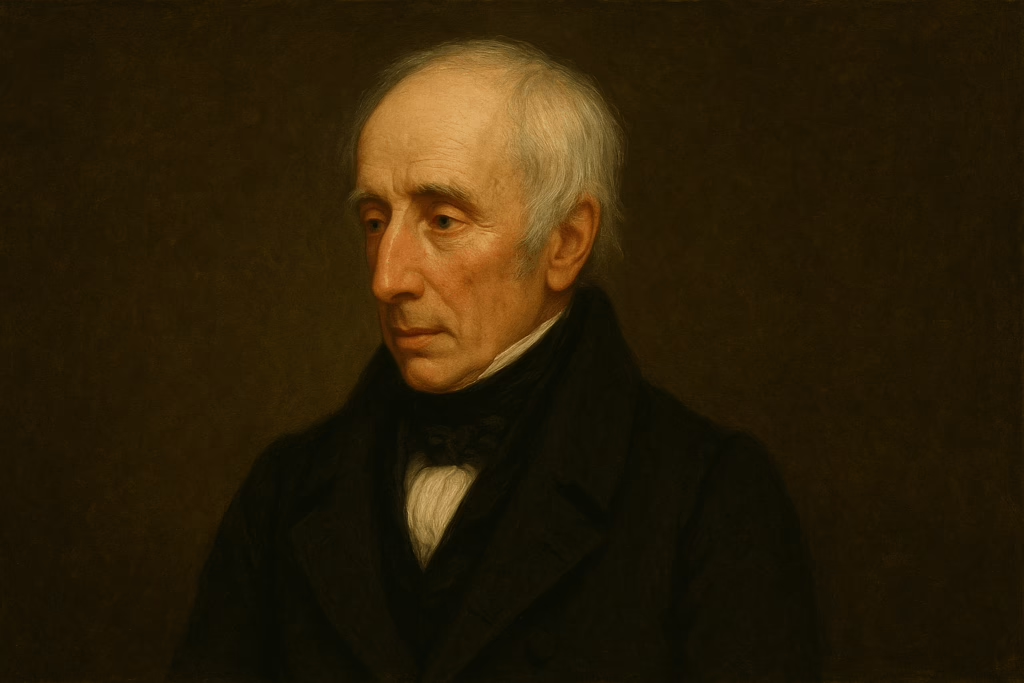

- William Wordsworth — Lyrical Ballads (1798, with Coleridge); Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey (1798); The Prelude (long autobiographical poem, composed in stages 1798–1805, published posthumously 1850); Ode: Intimations of Immortality (1807).

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge — The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798, in Lyrical Ballads); Kubla Khan (composed c. 1797, published 1816); Biographia Literaria (1817; critical prose).

- William Blake — Songs of Innocence (1789) and Songs of Experience (1794); The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790s).

- Lord Byron (George Gordon Byron) — Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (Cantos I–II 1812; later cantos), Don Juan (1819–24).

- Percy Bysshe Shelley — Ozymandias (1818), Ode to the West Wind (1819), Prometheus Unbound (1820), Adonais (1821).

- John Keats — Endymion (1818), Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems (1820), major odes (1819–1820) including Ode to a Nightingale, Ode on a Grecian Urn, To Autumn.

- Other notable poets: Robert Southey, Samuel Rogers, Thomas Moore, John Clare, Felicia Hemans, Charlotte Smith, Anne Finch (earlier but influential), Letitia Elizabeth Landon (L.E.L.).

2. The Novel (Romantic-era developments and Gothic)

- Jane Austen — Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814), Emma (1815).

- Mary Shelley — Frankenstein (1818) — Gothic + proto-Science Fiction, key Romantic critique of Promethean overreach and scientific ambition.

- Walter Scott — Waverley (1814), Ivanhoe (1819) — historical novel & medieval revival.

- Ann Radcliffe (earlier Gothic influence) and Matthew Lewis (The Monk) shaped the Gothic mode that Romantics both used and satirized.

3. Prose, Criticism, and Essays

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge — Biographia Literaria (1817), key Romantic criticism and theory.

- William Hazlitt — essays and dramatic criticism (later Romantic/early Victorian) — Characters of Shakespeare’s Plays (1817).

- Charles Lamb — Essays of Elia (collected 1823).

- Thomas De Quincey — Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821).

- Mary Wollstonecraft (pre-Romantic but influential) — Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792).

4. Drama, Masque, and Lyric Occasional Pieces

- Dramas were less central for the major Romantics, but Byron wrote Manfred (1817), a closet drama; Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound is a lyrical drama in four acts; and Keats wrote dramatic fragments. The period also contains masques and lyrical pieces performed privately.

5. Political and Philosophical Writings

- Shelley’s political poems and prose (A Defence of Poetry published 1840 posthumously; other political writings appear in periodicals).

- Byron’s letters and essays are politically engaged; his exile is politically consequential.

- Wordsworth and Coleridge wrote political pamphlets in their early careers.

IV. Close summaries of major works (essential for higher study)

This section provides concise but analytically rich summaries of the period’s most influential works, foregrounding formal features, themes, and interpretive entry points.

1. Lyrical Ballads (Wordsworth & Coleridge, 1798; 2nd ed. 1800; expanded 1802)

Importance: Often treated (by Wordsworth himself) as a foundational Romantic manifesto. The volume sought to use the “real language of men” and to treat subjects in common life with elevated feeling. Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Wordsworth’s rural lyrics (e.g., “Tintern Abbey” present in the 1798/1800 corpus and related pieces) show the period’s combined interest in archaic ballad forms, psychological depth, and moral vision.

Key points:

- The Preface (Wordsworth’s 1800/1802 expansions) articulates Romantic poetics: poetry as the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” and as the result of reflection on such feelings; poetry aims to connect the particular emotions of the speaker to general human experience via imaginative reconstruction.

2. William Wordsworth — Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey (1798) & The Prelude (composed 1798–1805; published posthumously 1850)

Tintern Abbey: A meditation on memory, nature, and self. Wordsworth contends nature’s moral and restorative powers, and the poem models a move from immediate sensuous joy to a maturity of reflective recollection.

The Prelude: An autobiographical epic that traces the growth of the poet’s mind, the formation of imaginative consciousness, and the moral relation between self and nature. The poem is a milestone in Romantic self-theory and in the idea of poetry as spiritual autobiography.

3. Samuel Taylor Coleridge — The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798); Kubla Khan (composed c. 1797; publ. 1816); Biographia Literaria (1817)

Rime: A narrative ballad combining supernatural horror, Christian redemption, and poetic diction; the mariner’s tale explores guilt, penance, and the power of imagination.

Kubla Khan: A fragmentary visionary lyric with opium-induced dream origins; the poem’s exotic imagery and syntax explore the imaginative act and the limits of poetic reproduction.

Biographia Literaria: Significant Romantic criticism; Coleridge theorizes imagination vs fancy, discusses poetic form and metaphysical philosophy, and weighs the nature of poetic language.

4. William Blake — Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1789 & 1794); The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (c. 1790)

Significance: Blake’s illuminated books fuse text and image; his visionary mythopoeia attacks institutional religion and modern rationalism, while celebrating imagination as prophetic insight. Songs present two states of the soul—innocence and experience—and interrogate the moral meaning of social institutions.

5. Lord Byron — Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (Canto I & II 1812)

Childe Harold: Byronic travel-hero poem that helped fashion the figure of the alienated, reticent, and world-weary hero. Byronic excess, irony, and cosmopolitan melancholy are hallmarks. Later works (Don Juan) expand satirical range and narrative vitality.

6. Percy Bysshe Shelley — selected lyrics and Prometheus Unbound (1820)

Ozymandias (1818): A sonnet about the ruins of a tyrant’s statue; it meditates on hubris, time, and the fate of empire.

Prometheus Unbound: A lyrical drama that reimagines the Prometheus myth as a liberatory allegory; Shelley fuses radical politics with metaphysical lyricism and imagistic fireworks.

Political poems: Shelley’s radicalism animates works that defend human freedom and imagined social transformation.

7. John Keats — Odes (1819), Endymion (1818), Lamia, The Eve of St. Agnes

Odes (1819): A cluster of intensely sensuous, philosophically profound lyrics (Ode to a Nightingale, Ode on a Grecian Urn, To Autumn, etc.) that interrogate beauty, mortality, transience, and the artist’s relation to the eternal.

Endymion: An ambitious but uneven epic romance, containing magnificent passages that display Keats’s rhetorical richness and sensuous imagination.

8. Mary Shelley — Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818)

Summary: A Gothic-science fiction novel that explores creation, responsibility, and alienation. Victor Frankenstein’s act of scientific hubris produces a creature rejected by society; themes include responsibility of creators, ethical limits of scientific experimentation, sympathy and monstrosity, and the social formation of identity.

Interpretive angles: Proto-Romantic anxieties about Enlightenment rationality; the novel as social critique; intertextuality with Promethean myth and Byronian / Shelleyan moral contexts.

9. Jane Austen — Pride and Prejudice (1813), Sense and Sensibility (1811)

Summary: Novels of manners that map social structures, marriage markets, and individuals’ moral characters. Austen’s irony, free indirect discourse, and social satire make her novels both realist documents of social relations and subtle moral narratives. Though often categorized separately from lyric Romanticism, Austen shares Romantic concerns (individual feeling, critique of modernity) even as she refuses grand poetic modes.

10. Walter Scott — Waverley (1814); Ivanhoe (1819)

Summary: Foundational historical novels that popularized medievalism and the historical romance; Scott’s novels blend antiquarian research and narrative invention, shaping national identities and nostalgia for premodern social orders.

V. Major themes and aesthetic principles

Romantic literature explores a set of recurrent themes and formal strategies that can be grouped heuristically.

1. Imagination and the Poetic Mind

- The imagination is the Romantic era’s central faculty (Coleridge’s distinction between fancy and imagination is canonical). Romantic poetics values creative synthesis, symbolic power, and the mind’s capacity to unite perception and moral insight.

2. Nature and the Sublime

- Nature is a pedagogic presence (Wordsworth), a sublime terror (the mariner’s sea), and a site for spiritual renewal. The sublime (awe mixed with terror) often appears in landscapes and metaphors (e.g., storm, abyss).

3. Subjectivity, Memory, and the Self

- Introspective autobiographical modes (Wordsworth’s Prelude) and lyric psychological portraits (Keats) treat memory as an instrument of meaning and poetic creation.

4. The Gothic, the Supernatural, and the Sublime Terrains

- Gothic modes (towers, ruins, monsters) express anxieties about modernity and the shadow side of Enlightenment rationality. The supernatural is a way to represent moral or psychological extremes.

5. Revolution, Politics, and Utopian Imagination

- From revolutionary enthusiasm to regret and radical critique, political engagement is central to much Romantic writing—Shelley’s radicalism, Byron’s exile, and Wordsworth’s shifting politics all demonstrate diverse political commitments.

6. Medievalism and National Past

- The medieval revival, especially in Scott, reimagined national cultural foundations and popularized the historical romance.

7. Gothic Science and the Promethean Motif

- Works like Frankenstein interrogate the ethical and social consequences of technological and scientific ambition; the Promethean trope is pervasive.

8. The Ballad Revival and Folk Cultures

- Interest in folk songs and ballads leads to the ballad form’s revival as a source of authenticity (Wordsworth/Coleridge’s ballad experiments) and inspires later antiquarian and folkloric scholarship.

VI. Formal and technical innovations

- Language: Shift toward colloquial diction in lyric and narrative, but also extravagant luxuriance in Keatsian lines and Shelleyan syntax.

- Prosody: Experimentation with blank verse, irregular stanza forms, and the ode as a flexible lyric form.

- Narrative modes: The rise of long poetic narratives, autobiographical epic (The Prelude), narrative novels with interior psychological realism (Austen), and the Gothic novel blending romance and terror.

- Intermediality: Increasing interaction with visual arts (Constable, Turner), music, and print culture; many poems read like paintings (ekphrasis).

VII. Critical reception and later influence

- Contemporary reception was mixed: some critics celebrated Romantic innovation (e.g., younger readers of Byron), while others attacked perceived excess and obscurity (e.g., conservative reviewers criticizing Shelley or Keats).

- By the mid-19th century, Romanticism’s influence was institutionalized through curricula and anthologies; Romantic poets became canonical (Wordsworth as poet laureate figure by mid-century).

- The Romantic emphasis on subjectivity and the imagination shaped later aesthetics: Victorian lyricism, modernism, and even contemporary critical approaches exploring subjectivity and the unconscious.

VIII. Representative chronology (selected dates)

- 1789 — French Revolution (inspiration for early Romantic politics).

- 1798 — Lyrical Ballads (Wordsworth & Coleridge) (often given as the starting point of English Romanticism).

- 1798 — Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey” (in the Lyrical Ballads-related corpus).

- c. 1797 — Coleridge composes Kubla Khan (not published until 1816).

- 1802 — Wordsworth publishes revised Preface (1800 preface earlier; 1802 revision) articulating Romantic poetics.

- 1812 — Byron’s Childe Harold (Cantos I–II).

- 1814 — Scott’s Waverley (foundational historical novel).

- 1816 — “Year Without a Summer” (volcanic winter after Tambora eruption) and the fateful summer at Geneva where Mary Shelley began Frankenstein.

- 1818 — Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1st ed.).

- 1819 — Peterloo Massacre (Manchester); Shelley composes The Masque of Anarchy.

- 1820–1822 — deaths of Byron’s continuing works; Keats (d. 1821), Shelley drowns in 1822.

- 1832 — Reform Act (political reform; end-of-period shifts consolidate).

- 1837 — Accession of Queen Victoria; this date often marks end of Romantic period in British literary periodization.

IX. Critical approaches and interpretive frameworks (advanced)

For graduate-level or advanced undergraduate study, the following critical lenses are productive:

- Romantic historicism: Contextualizing texts within political, economic, and social transformations (e.g., Ingres, industrialization).

- Psychoanalytic and subjectivity studies: Analyzing lyric interiority, visionary experience, dreams (Kubla Khan) and psychological projection (Byronic self).

- Ecocriticism: Reading Wordsworth, Clare, and others as critics of early industrial ecological change.

- Gender and feminist criticism: Investigating women writers, construction of gendered voice, and the domestic novel’s gender politics (Austen, Hemans, L.E.L.).

- Postcolonial readings: Exploring imperial encounters and representations (Byron’s travel poems, travel narratives, and the orientalism in Keats & Coleridge).

- Material book history & print culture: How periodicals, reviews, and publishing practices shaped authorial careers and reception.

X. Suggested reading list (primary texts and commentary)

Primary editions (recommended scholarly or reliable editions)

- William Wordsworth, Lyrical Ballads & The Prelude (Norton Critical Edition / Oxford Worlds Classics).

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Selected Poems & Biographia Literaria (Penguin/Everyman).

- William Blake, Songs of Innocence and of Experience (facsimile or annotated edition).

- Lord Byron, Selected Poems and Don Juan (Penguin / Oxford).

- Percy Bysshe Shelley, Selected Poems and Prometheus Unbound (Norton).

- John Keats, Complete Poems (Norton Critical).

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (Norton Critical, with contextual materials).

- Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice, Emma (Norton Critical Editions).

- Walter Scott, Waverley & Ivanhoe (Penguin Classics).

Secondary scholarship (introductory to advanced)

- M. H. Abrams, Natural Supernaturalism and The Mirror and the Lamp (classic Romantic theory).

- Jerome McGann, The Romantic Ideology (critical, historicist study).

- Duncan Wu (ed.), The Romantics: A Short Guide to Romanticism (introductory anthology/critical).

- Marilyn Butler, Romantics, Rebels and Reactionaries (historical perspective on politics and Romanticism).

- Anne Mellor, Romanticism and Gender (feminist perspectives).

- Jerome J. McGann and others on textual editing and bibliographical history (for archival and editorial approaches).

XI. Teaching modules and seminar ideas (advanced)

- Module: “Lyrical Self & Public World” — Pair Wordsworth’s The Prelude with Byron’s Childe Harold and Austen’s Pride and Prejudice to discuss private feeling vs public social life.

- Module: “Gothic, Science, and Ethics” — Frankenstein alongside contemporary scientific essays and Shelley’s political poetry.

- Module: “Nature and the Industrial Revolution” — Wordsworth, Clare, and selected social reports on enclosures and labor.

- Seminar: “Women and Romanticism” — Charlotte Smith, Mary Wollstonecraft, Jane Austen, Felicia Hemans, Letitia Landon; consider gendered publication practices and reception.

XII. Conclusion

The Romantic Period (1798–1837) is both an era of intense aesthetic innovation and a historical moment of high emotional stakes. Romantic writers refigured the role of imagination, created new lyrical genres and narrative forms, and engaged actively with their historical moment—politically, philosophically, and ethically. They remain central to literary studies because they redefine what literature can do: to feel deeply, to imagine alternatives, to critique social arrangements, and to re-enchant the world.