The Edwardian Age — conventionally dated from the death of Queen Victoria in 1901 to the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 — is a compact but pivotal moment in the history of English literature. It is at once the last phase of late-Victorian culture and a prelude to modernism. In these thirteen years authors and poets continued many Victorian preoccupations (class, empire, moral earnestness, realism) but also registered accelerating technological change, new political ferment, emergent feminist consciousness, and a mood of aesthetic restlessness. The result was literature that often looks backward with nostalgia and forward with unease: a literature of transition in form as well as theme.

This chapter is written for higher-study students. It sets out the Edwardian historical map and explains the principal literary consequences; offers an ordered taxonomy of writers and their important works; supplies careful summaries and interpretive entry points for major texts; surveys principal themes and formal tendencies; and concludes with pedagogic suggestions and an annotated bibliography for further reading.

1. Historical, social and cultural background (major events and their literary impacts) in the Edwardian age

Any study of Edwardian literature must be placed against rapid and sometimes contradictory changes in British society. The items below list the most salient political, social and technological events of the period and indicate how they shaped the imaginative literature of the age.

1.1 The death of Queen Victoria and a new epoch (1901)

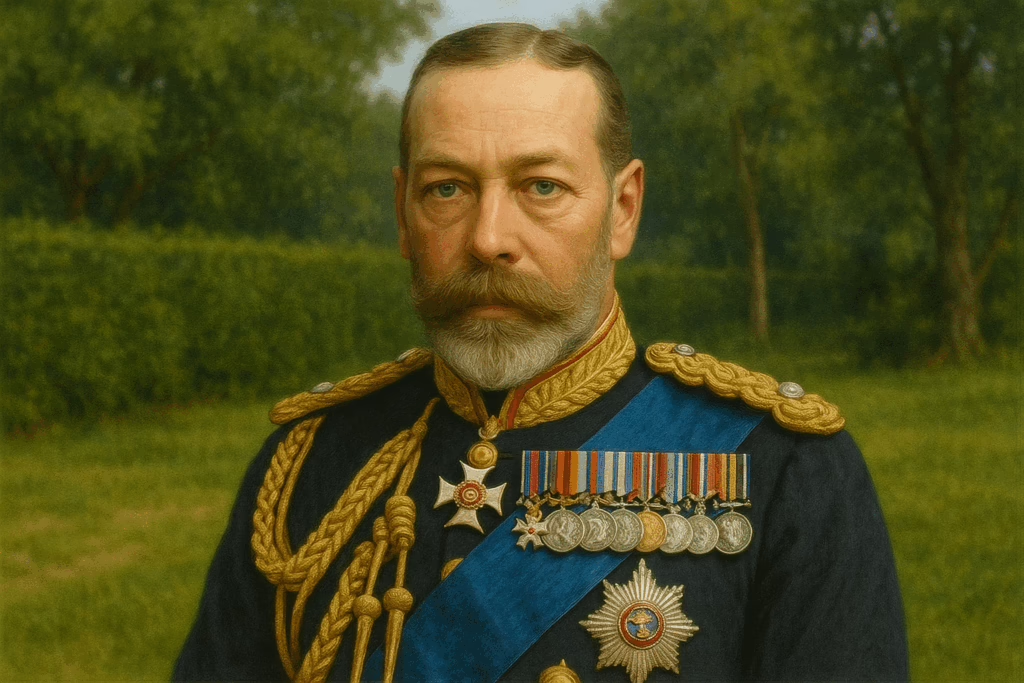

- Event (1901): The passing of Victoria and the accession of Edward VII signalled a clear chronological break.

- Literary impact: The shift from the long Victorian century to a shorter, more urban and cosmopolitan Edwardian moment encouraged writers to reassess Victorian certainties about duty, empire and moral certitude. Many Edwardian works register nostalgia for “an older order” while scrutinising its hypocrisies.

1.2 The Boer War and the imperial conscience (1899–1902; repercussions into Edwardian years)

- Event: The war in South Africa exposed the human and moral cost of imperial policy.

- Literary impact: The trauma of war produced sceptical reflections on imperial heroism. Writers — poets, journalists and novelists — began to question jingoism and celebrate, or at least probe, the ethical ambiguities of empire (a notable effect in the work of H. G. Wells and Joseph Conrad).

1.3 Social reform and party politics (1906–1911)

- Events: Liberal landslide of 1906; the Old-Age Pensions Act (1908); National Insurance Act (1911); the constitutional crisis over the House of Lords and the Parliament Act (1911).

- Literary impact: The expansion of state welfare and the intensification of parliamentary politics focussed literary attention on class conflict, social responsibility and the tensions between public reform and private life. Novelists used social realism to stage moral debates about responsibility and modernity (Forster, Galsworthy, Bennett).

1.4 Women’s suffrage and the New Woman (early 1900s to 1914)

- Event: Suffrage organisations, primarily the militant Women’s Social and Political Union (founded 1903), campaigned energetically.

- Literary impact: The New Woman became a recurrent figure in Edwardian fiction and drama: novels and plays began to stage female autonomy, education and sexuality in new ways. Writers interrogated marriage laws, women’s employment, and the constraints of domestic ideology (Forster, Shaw, Barrie, some popular fiction).

1.5 Labour movement, trade unionism and the rise of Labour (1900s)

- Events: Organised labour gained influence; the Labour Party developed into a parliamentary presence.

- Literary impact: Working-class life, industrial conflict and social justice entered the literary agenda more explicitly; realism turned its gaze to urban poverty and the factory economy (Galsworthy, Gaskell’s legacy, lesser-known social novelists).

1.6 Technological advance, transport and communications

- Events: Automobiles, aviation (the Wright brothers’ flights from 1903 and subsequent progress), wireless telegraphy and improved mass-print technology.

- Literary impact: New technologies appear as themes and metaphors (Wells’s mechanised apocalypses, later novels about aerial warfare), and the compression of space and time (railways, cables) recasts urban and imperial imagination. Serialisation and magazine culture depended upon advances in printing.

1.7 Culture, leisure and the arts

- Events: The flourishing of London theatre; the persistence of aestheticism and the early stirrings of modernist experimentation in art and poetry; the popularity of seaside holidays and the ‘leisure industry’.

- Literary impact: Dramatic innovation (Shaw’s plays), children’s fantasy (Barrie), and a vigorous popular press fed a diversified literary marketplace. At the same time, a new appetite for shorter lyric and “pictorial” modes prepared readers for later developments.

1.8 International tensions

- Events: Naval rearmament and Anglo-German rivalry in the decade before 1914; European diplomatic tensions.

- Literary impact: The atmosphere of competition and apprehension finds reflection in dystopian and futuristic writing (Wells), in patriotic verse (Rupert Brooke and some Georgian poets), and — after 1914 — in the traumatic reorientation of British letters.

2. Periodisation and subdivisions of Edwardian literature

The Edwardian phenomenon is brief; nonetheless scholars commonly separate it into two overlapping phases for analytical clarity:

- Early Edwardian (c. 1901–1907). Continuities with late Victorian forms: long realist novels, social comedy, moral earnestness. Writers still often used omniscient narration and conventional plots. The early phase retains Victorian confidence in ethical improvement and in art’s educational role.

- Late Edwardian / Pre-war (c. 1908–1914). Increasing scepticism and social agitation: suffrage militancy, intensified union action, the constitutional crisis, and cultural radicalism. Stylistic experiments and psychological inwardness become more frequent. Authors register pre-war anxiety; some literary modes (children’s fantasy, experiment in lyric simplicity) anticipate modernism.

These two phases overlap and are not absolute: individual authors move between tones and practices.

3. Print culture, periodicals and the marketplace

Edwardian literature operated in an extremely active print culture. Key features:

- Serialisation. Many novels first appeared in monthly or weekly instalments in magazines. Serialization affected narrative pacing (cliff-hangers, episodic structure) and shaped readership expectations.

- Mass periodicals. Titles such as The Strand, Cassell’s, T. P.’s Weekly, Nash’s, The Fortnightly Review and The English Review provided forums for fiction, essays and criticism. Popular short fiction (detective stories, adventure tales) coexisted with serious essays and literary criticism.

- Little magazines and reviews. A growing number of smaller, more literary journals emerged to present unconventional work (precursors to the modernist little magazines that would flourish after 1914).

- Book clubs and lending libraries. Mudie’s and circulating libraries influenced what readers saw in their homes and helped determine commercial success.

The result was a tiered literary market: highbrow criticism, respectable middle-class fiction and a large popular culture of genre fiction.

4. Major writers and works (categorical survey + short summaries)

Below is a structured list of the principal British writers associated with the Edwardian years, grouped by principal practice. Each entry contains a short description of key works and interpretive notes appropriate for advanced study.

Note: Several influential works written slightly before 1901 remain formative in the Edwardian imagination (e.g. Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Wells’s early SF). This chapter prioritises works published in or closely associated with 1901–1914, but it also recognises continuities.

4.1 Novelists and major prose writers

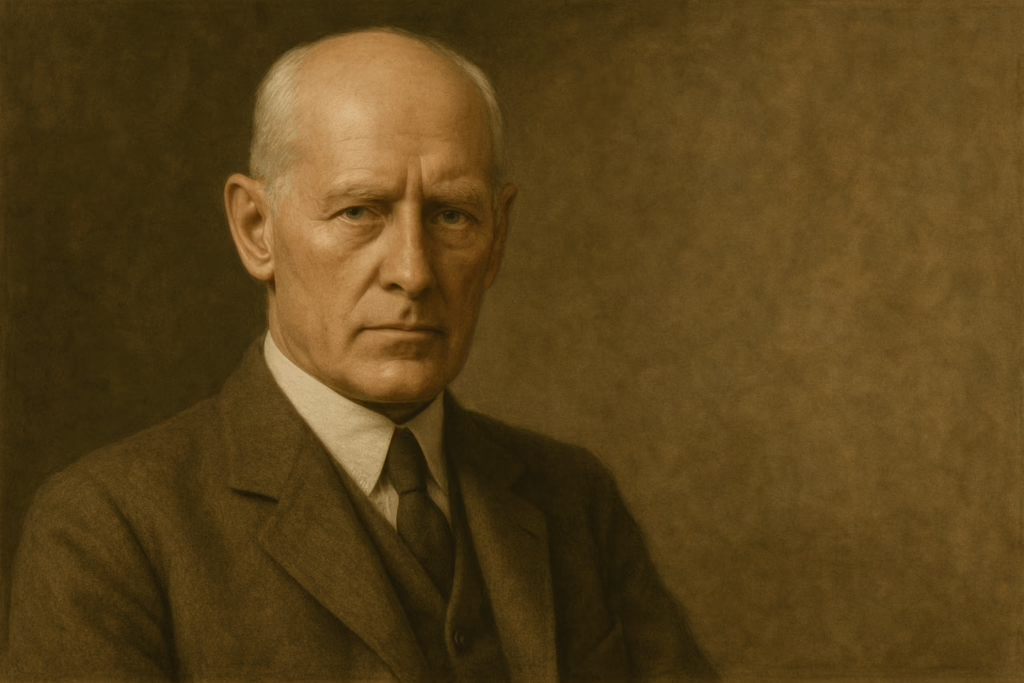

E. M. Forster (1879–1970)

- Representative Edwardian works:

- Where Angels Fear to Tread (1905) — Forster’s first novel; a critical study of middle-class English provincialism observed through the calamities that befall an Englishwoman in Italy.

- The Longest Journey (1907) — A study of vocation and artistic calling, with complex moral conflicts.

- A Room with a View (1908) — A social comedy about English reserve, personal awakening and the tensions between social convention and spontaneous feeling. Lucy Honeychurch’s exposure to Italy catalyses a reassessment of English propriety.

- Howards End (1910) — A mature novel juxtaposing three households (the idealistic Schlegels, the conservative Wilcoxes, and the practical Basts) to interrogate property, social responsibility and human connection. The famous injunction “Only connect…” (at the novel’s centre) encapsulates Forster’s moral aim.

- Critical significance: Forster combines social comedy with moral humanism; his technique of psychological observation and social critique makes him a bridge figure from late Victorian realism to later modernist preoccupations with interior life and social symbol.

John Galsworthy (1867–1933)

- Representative Edwardian works:

- The Man of Property (1906), first volume of The Forsyte Saga — A panoramic social novel on bourgeois possession and the cost of materialist ethics. Soames Forsyte’s view of marriage as property is a catalyst for tragedy.

- Later instalments trace the family through shifting social and moral climates.

- Critical significance: Galsworthy’s panoramic realism and his moral indictment of bourgeois values made him a prominent Edwardian chronicler of the property ethos.

Arnold Bennett (1867–1931)

- Representative Edwardian works:

- The Old Wives’ Tale (1908) — A realist epic that traces two sisters across the late 19th and early 20th centuries; explores domestic endurance, modernity, and provincial life in the Potteries (Staffordshire).

- Clayhanger (first volumes 1910) — A portrait of provincial professional life and social aspiration.

- Critical significance: Bennett’s attention to “the ordinary” and to provincial modernity stresses the Edwardian interest in social detail and the impact of change upon everyday people.

H. G. Wells (1866–1946)

- Representative Edwardian works:

- The War in the Air (1908) — A speculative novel anticipating air warfare and technological destruction.

- Tono-Bungay (1909) — A semi-autobiographical social novel satirising profiteering, advertising and middle-class ambition; a critique of capitalist modernity.

- The History of Mr. Polly (1910) — A social novel with comic pathos; a humane study of a lower-middle-class clerk’s discontents.

- Critical significance: Wells blends imaginative speculation with social critique. His popular science-fiction scenarios also function as ethical fables about technology and imperialism.

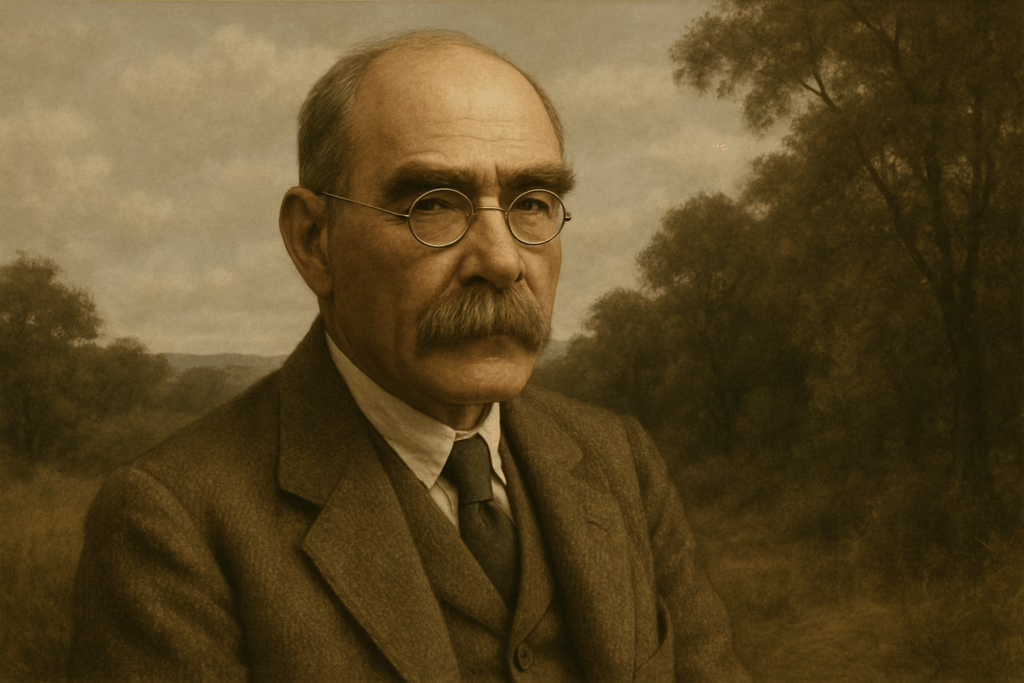

Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936)

- Representative Edwardian works:

- Kim (1901) — An adventure novel set in colonial India; combines espionage plot with rich ethnographic detail.

- Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906) and Rewards and Fairies (1910) — Collections of nostalgic tales drawing upon English national myth.

- Critical significance: Kipling’s complex imperial imagination — sometimes celebratory, sometimes reflective — dominated much Edwardian public sentiment. Kim in particular remains central for studies of empire and identity.

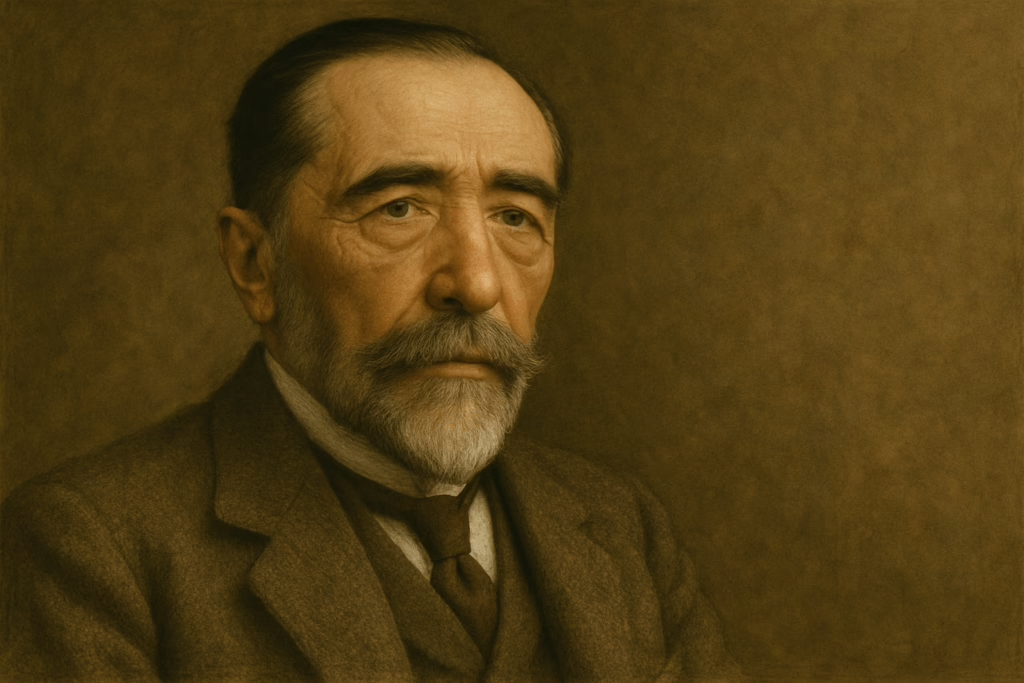

Joseph Conrad (1857–1924) (Polish by birth; English by language and domicile)

- Representative works in the Edwardian context:

- Lord Jim (1900) and later stories; while written around the turn of the century, Conrad’s narrative techniques and moral focus deeply influenced Edwardian and post-Edwardian prose.

- Critical significance: Conrad’s interrogation of imperial violence, his ironic distance and narrative fragmentation anticipate modernist concerns.

Other novelists and popular writers

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle — Sherlock Holmes stories and adventure novels continued to appear in magazines and books; Doyle’s prolific popular fiction shaped serial narrative taste.

- John Buchan — emerged as an author of thrillers slightly after 1914, but his early journalism and popular fiction fed an audience for espionage and imperial adventure.

- A. S. M. Hutchinson, H. Rider Haggard, G. A. Henty — representatives of popular Edwardian fiction and imperial romance.

4.2 Dramatic writers and the stage

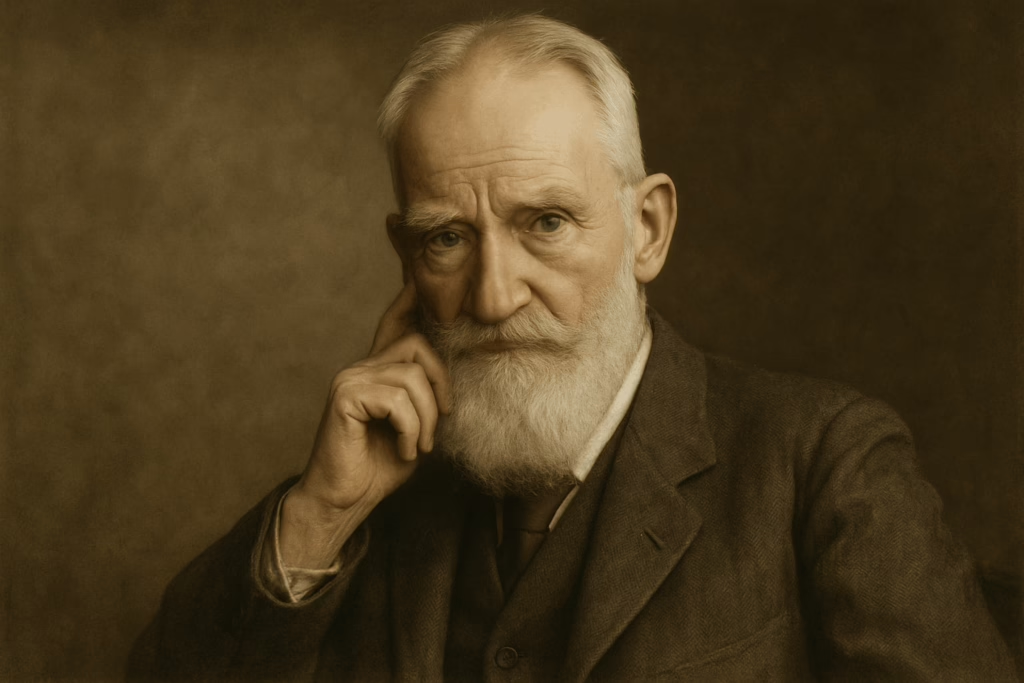

George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950)

- Representative Edwardian plays:

- Man and Superman (1903) — A philosophical comedy exploring social duty and the “life force.” The play contains the famous “Don Juan in Hell” dream scene.

- Major Barbara (1905) — Themes of morality, wealth and social ethics: a Salvation Army heroine confronts the paradoxes of poverty relief funded by armaments magnates.

- Pygmalion (1913–14) — A social satire on class and linguistic performance; Shaw’s comedy highlights the social construction of identity.

- Critical significance: Shaw fused polemic with theatrical craft; his plays used wit to interrogate social institutions and moral complacency. His dramatic method combined didactic aims with lively stagecraft, engaging middle-class audiences.

J. M. Barrie (1860–1937)

- Representative Edwardian play:

- Peter Pan; or, The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up (stage debut 1904; novelisation 1911) — A fantasy play about childlike freedom and the bittersweet pains of adulthood.

- Critical significance: Barrie’s blend of fantasy, nostalgia and social observation made Peter Pan one of the enduring dramatic works of the era. It also addresses parenthood, loss and the politics of childhood innocence.

Other playwrights

- Arthur Wing Pinero, Harley Granville-Barker and others worked in the Edwardian theatre, producing social comedies and naturalistic dramas. The London stage was vibrant: public taste for both social satire and escapist entertainment remained strong.

4.3 Poets and lyricists

Poetry in the Edwardian years sits between late-Victorian elaboration and the nascent simplicity of the Georgian poets and the later modernists.

Rupert Brooke (1887–1915)

- Representative poems: His patriotic sonnets written in 1914 (posthumously popularised) — “The Soldier” — epitomised romantic patriotism and the “before war” mood of idealised sacrifice.

- Critical significance: Brooke became a symbol of Edwardian optimism and the romantic heroism later ruptured by the First World War.

Thomas Hardy (1840–1928) (not primarily an Edwardian poet but produced important late poetry)

- Representative Edwardian output: Poems of the Past and Present (1912) and other collections. Hardy’s verse often mourned rural change and registered personal loss and social irony.

Georgian poets (emerging at the end of the Edwardian period)

- A first anthology, Georgian Poetry (1912–13), collected young poets whose simple diction and nature-led themes offered a conservative alternative to late-Victorian Romantic excess. Their prominence rose shortly after 1912.

Other poets

- Alfred Noyes, Robert Bridges and others published verse that moved variously between tradition and new sensibility. Although modernist upheaval lay ahead, the Edwardian lyric is notable for its range — from the conservative to the anticipatory.

4.4 Essayists, critics and intellectual writers

- G. K. Chesterton — essays, novels and detective stories blending paradox, Catholic sympathies and cultural commentary.

- Hilaire Belloc and A. E. Housman (poetry and scholarship) were active; Arnold Bennett and H. G. Wells also contributed essays on social reform.

5. Short summaries and close-reading entry points for selected major works

The following summaries are designed for seminar use and include suggested angles of interpretation.

5.1 Howards End (E. M. Forster, 1910)

- Plot and structure: Centers on the Schlegels (intellectual and liberal), the Wilcoxes (conservative, capitalist), and Leonard Bast (a lower-middle-class clerk). The novel examines property, connection and social responsibility through events such as inheritance, thwarted relationships and the mysterious house, Howards End.

- Themes: Class friction, the human necessity of connection (“Only connect…”), property and ethics, the failure of pure rationalism to secure humane relations.

- Critical angles: The novel’s ironic narrator; the house as symbol and moral centre; Forster’s critique of economic liberalism; the representation of gender and mental health.

5.2 The Man of Property (John Galsworthy, 1906)

- Plot and structure: The first part of The Forsyte Saga focuses on Soames Forsyte’s possessive marriage to Irene, which becomes a case study in bourgeois materialism.

- Themes: Property and possession as central organising principles; legalism vs. human freedom; the emotional cost of commodification.

- Critical angles: Galsworthy’s social realism; his ethical scepticism; narrative treatment of women’s autonomy.

5.3 Tono-Bungay (H. G. Wells, 1909)

- Plot and structure: A partly autobiographical narrative of a man swept up in the inventive capitalist world of a patent medicine; a critique of advertising, speculation and moral compromise.

- Themes: The corrosive effect of cynical capitalism; the ethics of invention and popular success; satire of Edwardian social life.

- Critical angles: Wells’s use of the unreliable narrator; the novel as social prophecy; the figure of the charlatan entrepreneur.

5.4 Kim (Rudyard Kipling, 1901)

- Plot and structure: The orphan Kim travels across the subcontinent, becoming involved in espionage during the “Great Game.” The novel interweaves adventure with meditations on identity and cultural hybridity.

- Themes: Imperial governance and ambivalence; cultural assimilation and curiosity; the tension between innocence and political knowledge.

- Critical angles: Kipling’s portrayal of colonial India; questions of racial and national identity; novelistic ethics in representing the colonised.

5.5 Plays by George Bernard Shaw (selected)

- Major Barbara: A debate play that stages social ethics (wealth vs. charity). The play explores whether “the means of making the world habitable for the poor” are morally tenable when funded by weapons makers.

- Pygmalion: Explores language as a social shaper. The transformation of Eliza Doolittle interrogates the social currency of speech and the fragility of class distinction.

6. Principal themes and formal tendencies

6.1 Social realism and the novel of social critique

- Tendency: The Edwardian novel continued realism’s close observation of social milieux but often added moral urgency and a new psychological subtlety (Forster’s inwardness; Galsworthy’s family panorama; Bennett’s provincial detail).

6.2 The problem of empire

- Tendency: Writers treated empire as setting, object of critique, and ethical puzzle. Conrad and Wells often highlight imperial violence; Kipling mixes celebration with critique; Galsworthy and Forster question metropolitan complacency.

6.3 Gender, the New Woman and domestic modernity

- Tendency: Fiction and drama staged women’s struggle for autonomy. Shaw’s plays and Forster’s novels showcase women who challenge convention; Barrie and others reconsider childhood and domestic roles.

6.4 Science, technology and anxiety

- Tendency: Technological advance is ambivalently represented. Wells’s speculative fictions warn of mechanised destruction; aviation and wireless changes filter into the metaphors of many writers.

6.5 Nostalgia and aesthetic retreat

- Tendency: Barrie’s fantasy and Kipling’s historical tales show a yearning for earlier times; simultaneously, many authors deployed irony towards nostalgia.

6.6 Seeds of modernism: inwardness, fragment and form

- Tendency: Although full modernist rupture occurs after 1914, Edwardian writing often experiments with perspective, voice, and symbol. Forster’s narrative irony and Forster’s psychological realism both anticipate later stream-of-consciousness and symbolist modes.

7. Style, narrative technique and formal innovation

- Continuities: Most Edwardian novels use relatively conventional narrators, realist description and linear plotting. Serialization shaped pacing and suspense.

- Innovations: Increased attention to interior life, sympathetic free indirect discourse, and montage-like episodes. Conrad’s narrative fragmentation and unreliable narrators influenced later experimentation. Playwrights such as Shaw broadened the dramatic essay into stage form; Barrie used fantasy and nostalgia to explore psychological loss. Poets moved toward simpler diction (the Georgian tendency) and new concerns with image and lyric immediacy.

8. Pedagogy, seminar themes and graduate research topics

8.1 Suggested seminar clusters

- Class and property: Forster’s Howards End, Galsworthy’s The Man of Property, and selected essays by late-Victorian critics.

- Empire and ethics: Conrad, Kipling’s Kim, Wells’s imperial allegories.

- Gender, suffrage and the New Woman: Shaw’s Pygmalion, Barrie’s Peter Pan, selected Forster novels, contemporary suffrage reporting.

- Children and nostalgia: Barrie’s Peter Pan, popular Edwardian children’s fiction and its cultural resonance.

- Proto-modernism: Close readings of narrative voice in Conrad and Forster; Georgian lyric precursors; textual study of periodical avant-gardes.

8.2 Graduate research topics (examples)

- “Soames Forsyte and the commodification of marriage: property law and narrative ethics.”

- “Technological prophecy in Wells: aviation, wireless and the imagination of total war before 1914.”

- “The stage as platform: Shaw’s dramaturgy and the public pedagogy of social reform.”

- “The New Woman in Edwardian fiction: narrative strategies and ideological conflict.”

- “Serialisation and narrative form: how magazine instalments shaped Edwardian novelistic temporality.”

9. Annotated bibliography (recommended editions and scholarship)

Primary texts (recommended scholarly editions)

- Forster, E. M., Howards End (Penguin Classics, critical edition).

- Galsworthy, John, The Forsyte Saga (Penguin modern classics; individual volumes) — see The Man of Property.

- Bennett, Arnold, The Old Wives’ Tale (Penguin/Everyman).

- Wells, H. G., Tono-Bungay (Oxford World’s Classics) and The War in the Air (Penguin).

- Kipling, Rudyard, Kim (Penguin Classics).

- Conrad, Joseph, Lord Jim and Heart of Darkness (Penguin Classics).

- Shaw, G. B., Plays (Penguin/Everyman editions).

- Barrie, J. M., Peter Pan & Other Plays (Oxford World’s Classics).

Secondary reading (introductory to advanced)

- Michael Holroyd, A Strange Eventful History: The Dramatic Lives of Kenneth Tynan (for theatre context).

- Adrian Wright, The Edwardian Aristocracy and the Literary World (contextual essays).

- David Trotter, Literature in the 1900s: The Edwardian Period (survey and criticism).

- John Lucas, The Radical Twenties: British Literature and Culture Between the Wars (for transitions beyond 1914).

- Peter Faulkner, Theatre and Society in Edwardian Britain (theatrical context).

(Students should consult specialist monographs on individual authors for detailed textual, archival and theoretical work.)

10. Examination questions and essay prompts (advanced level)

- “Discuss the ways in which Howards End stages social responsibility and property. How does Forster’s narrative technique mediate his moral argument?”

- “Compare and contrast the treatment of empire in Rudyard Kipling’s Kim and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (or later Conrad works). What differing ethical positions do the two authors take?”

- “Examine George Bernard Shaw’s dramatic method in Major Barbara. How does Shaw use stagecraft to argue a moral point?”

- “Assess H. G. Wells’s critique of capitalist modernity in Tono-Bungay. In what ways does Wells anticipate later modernist treatments of technology?”

- “The New Woman is a central figure of early 20th-century fiction. Analyse representations of female agency in an Edwardian novel or play.”

11. Final advice for higher-study students

- Read primary texts closely — pay attention to narrative voice, structure and the social detail that realist writers deploy as cultural evidence.

- Contextualise historically — Edwardian literature is best understood in relation to political reforms, the suffrage movement, and imperial tensions.

- Compare genres — serial fiction, drama and poetry operate with different constraints; contrasts illuminate the era’s cultural economy.

- Trace continuities and breaks — situate Edwardian texts both as inheritors of Victorian forms and as ancestors of modernist innovation.

Conclusion: the Edwardian bridge

The Edwardian Age is essentially a literary and cultural bridge. It preserves Victorian moral seriousness and narrative craft while beginning to accommodate aesthetic fragmentation, psychological complexity, and social scepticism that will mature after 1914. Its short duration makes it a concentrated study: the period contains confident narratives of empire and prosperity as well as unmistakable signs of doubt and disquiet. For students of literature the reward of studying Edwardian texts is the chance to observe the moment when nineteenth-century realism and moral discourse yield, in embryo, the experimental forms and thematic anxieties that will define twentieth-century British literature.