The Georgian Age in British literary history — conventionally dated 1910–1936 — describes a distinctive phase between late Victorian/Edwardian culture and the full flowering of modernism. The term is most often associated with a group of poets collected in the Georgian Poetry anthologies (edited by Edward Marsh) and with a broader constellation of writers whose work answered the dramatic social, political and technological changes of the early twentieth century: first and foremost the First World War, but also suffrage, labour politics, the decline of old certainties, the expansion of mass culture, and the intensifying debates about empire and national identity.

This chapter offers a comprehensive account of the Georgian Age for higher studies. It includes: (1) a chronological map of major historical events and their literary effects; (2) suggested subdivisions of the period and their characteristic tendencies; (3) a categorical survey of principal authors and representative works, with short analytical summaries; (4) thematic and formal analysis (poetry, narrative, drama, periodicals); (5) suggested scholarly approaches, seminar topics and research questions; and (6) an annotated bibliography and pedagogic resources. The treatment foregrounds British literature and places the Georgian poets and their contemporaries in relation to the overlapping currents of war poetry, modernism and inter-war literary culture.

1. Major historical events (1910–1936) and literary impacts

The dates 1910–1936 map onto a period of intense political and cultural turbulence whose artistic consequences were immediate and long-lasting.

1.1 Constitutional and social tensions (1910–1914)

- Events: Constitutional crisis (House of Lords v. Commons), 1910 elections; suffrage agitation; labour militancy.

- Literary impact: The pre-war years record a heightened interest in social reform, political satire and the “New Woman” in fiction and drama. Writers stage class and gender tensions more directly than many fin-de-siècle predecessors.

1.2 The First World War (1914–1918)

- Event: Industrialised total war with unprecedented scale of military casualties and social disruption.

- Literary impact: The war marks a decisive rupture. War poetry becomes central: the pathos and sarcasm of Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen challenged romantic notions of martial glory; Rupert Brooke’s early patriotic verses gained iconic status before being displaced by disillusioned, brutally realistic verse. The war also transformed the novel — both through direct representations of combat and through an intensified interest in trauma, memory and alienation. The conflict accelerated the collapse of certainties about empire, progress and moral purpose and produced a body of literature characterised by grief, irony and ethical questioning.

1.3 Revolution abroad and political aftershocks (1917–1920s)

- Events: Russian Revolution (1917), post-war revolts, Irish Easter Rising (1916) and subsequent struggle for independence (1919–1921).

- Literary impact: Revolutionary politics influenced intellectual debate in Britain, shaped radical writing and compelled authors to reconsider social utopias and the limits of liberal reform. The Irish question invigorated poetry and drama in and about Ireland, and it reconfigured British-Irish literary relations.

1.4 Post-war settlement and social reform (1918–1929)

- Events: Representation of the People Act (1918) enfranchised many men and, in part, women; the Equal Franchise Act extended the franchise to women in 1928; demobilisation, economic struggles, and partial welfare reforms followed.

- Literary impact: Post-war novels and poems examine the social costs of wartime sacrifice; literature engages with gendered social change and the politics of return and re-integration. New voices — including women writers and working-class narrators — become more prominent.

1.5 Cultural modernisation, mass culture and new media

- Events: Expansion of cinema and radio; broader literacy and mass-market print culture.

- Literary impact: Authors adapted to new markets; short stories, essays and serialized fiction circulated widely. The period also saw the emergence of little magazines and modernist journals (some overlapping into Georgian years), which offered experimental writers outlets for formal innovation.

1.6 The Great Depression and rising political extremism (1929–1936)

- Events: Worldwide economic slump after 1929: unemployment and political instability grew. The 1930s also saw the rise of fascist movements in Europe.

- Literary impact: Economic crisis sharpened political literature: socialist and anti-fascist writing flourished; writers debated art’s social function. The inter-war novel grapples with fragmentation, uncertainty and the search for cultural remedies.

2. Subdivisions and period logic

Because the Georgian Age spans more than two turbulent decades, it is analytically useful to subdivide it into overlapping phases while recognising continuity across them.

A. Pre-war and early Georgian (c. 1910–1914)

- Characteristics: Pastoral lyric and traditional forms (the “Georgian” pastoral), Edwardian continuities, rising social criticism. Edward Marsh’s first Georgian Poetry volume (1912) formalised a taste for plain language, nature lyric and convivial tone.

B. War and immediate aftermath (1914–1920)

- Characteristics: Intense literary engagement with combat, trauma and loss; the rise of trench poets and autobiographical memoirs; the disillusionment of veterans becoming a key cultural theme.

C. High inter-war and modernist consolidation (1920–1929)

- Characteristics: Modernist innovations crystallise (T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf), while many Georgian poets continue in a conservative lyric vein. New social novels (Forster, Galsworthy, Bennett) and experimental prose appear side by side.

D. Late inter-war, political crisis and literary radicalism (1930–1936)

- Characteristics: The Depression years produce socially engaged fiction and poetry; politically committed writing (anti-fascist, leftist) gains prominence; the Georgian label fades into the background as modernism asserts its dominance.

These subdivisions help to map movements, but writers often move between idioms: some Georgian poets matured toward more modernist styles; some modernists retained lyric attachments to nature.

3. Defining the Georgian poets and the anthology impulse

The label “Georgian” derives from the anthologies titled Georgian Poetry, edited by Edward Marsh and published between 1912 and the early 1920s. Marsh, who served in political circles and became a patron of poets, sought to present a counterpoint to the highly allusive, urban modernist verse associated with certain contemporaries. Georgian poetry emphasised:

- Plain diction and accessible imagery.

- Pastoral and rural subjects, nostalgia for country life.

- Musical and narrative lyric forms (ballad, sonnet, short narrative lyric).

- An avoidance (at least in intention) of the dense allusiveness of poets like T. S. Eliot.

The anthologies collected a wide range of poets: some were minor figures, others later attained larger reputations. The label is useful but imprecise; many “Georgian” poets wrote important war poetry and nuanced lyric beyond mere pastoral sentiment.

4. Major authors and works (categorical survey with summaries)

The Georgian Age comprises a rich and heterogenous body of writing. The material below organises principal authors into categories — poets (Georgian & war), novelists and short-story writers, dramatists and playwrights, essayists and critics — and supplies short summaries and interpretive signposts suitable for graduate study.

Caveat: The period overlaps with modernist developments; many canonical modernist works (Joyce, Eliot, Woolf) fall within or close to this timeframe and are included here to show the co-existence and contest between Georgian pastoralism and modernist experimentation.

4.1 Poets

A. Georgian-label poets and pastoral lyricists

- Edward Marsh (editorial influence) — not a poet of note but the driving editorial figure behind the Georgian Poetry volumes; his patronage shaped tastes and careers.

- John Masefield (1878–1967)

- Representative works: Sea-Poems and lyrics; “Sea-Fever” (I must go down to the seas again), pastoral and maritime lyrics.

- Significance: Masefield’s lyrical command and sea-poetry captivated popular taste; later appointed Poet Laureate (1930).

- Walter de la Mare (1873–1956)

- Representative works: “The Listeners,” children’s and uncanny lyrics; Peacock Pie (children’s verse).

- Significance: De la Mare’s imaginative, uncanny childhood lyric and short poems combine simplicity and psychological depth.

- Rupert Brooke (1887–1915)

- Representative works: Sonnet sequence including “The Soldier” (1914).

- Significance: Brooke’s early idealistic sonnets (written before his death in 1915) became emblematic of pre-war patriotic feeling; his premature death consolidated his symbolic status.

- Other Georgian-associated poets: H. A. Saintsbury; Wilfrid Gibson; Lascelles Abercrombie; Robert Graves (early career overlaps with Georgian collections); Julian Grenfell (war poet, killed in 1915).

B. War poets (overlap with Georgian label, but thematically distinct)

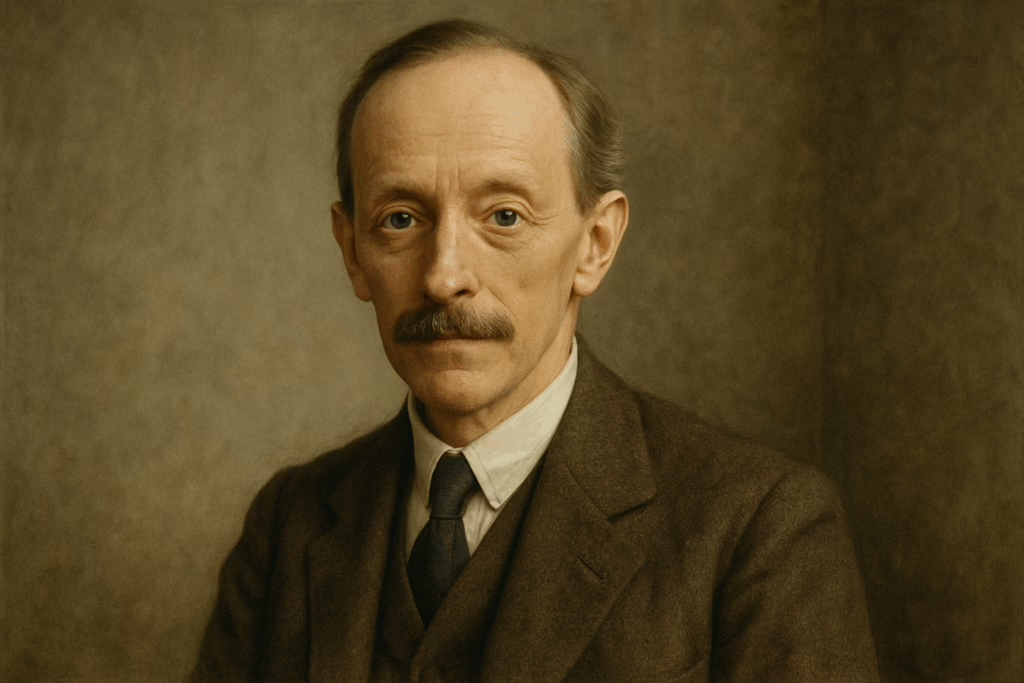

- Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967)

- Representative works: Counter-Attack, The War Poems — biting, satirical, and often autobiographical verse decrying war’s waste.

- Significance: Sassoon’s public protest and verse of bitter irony and moral crisis shaped British responses to the war.

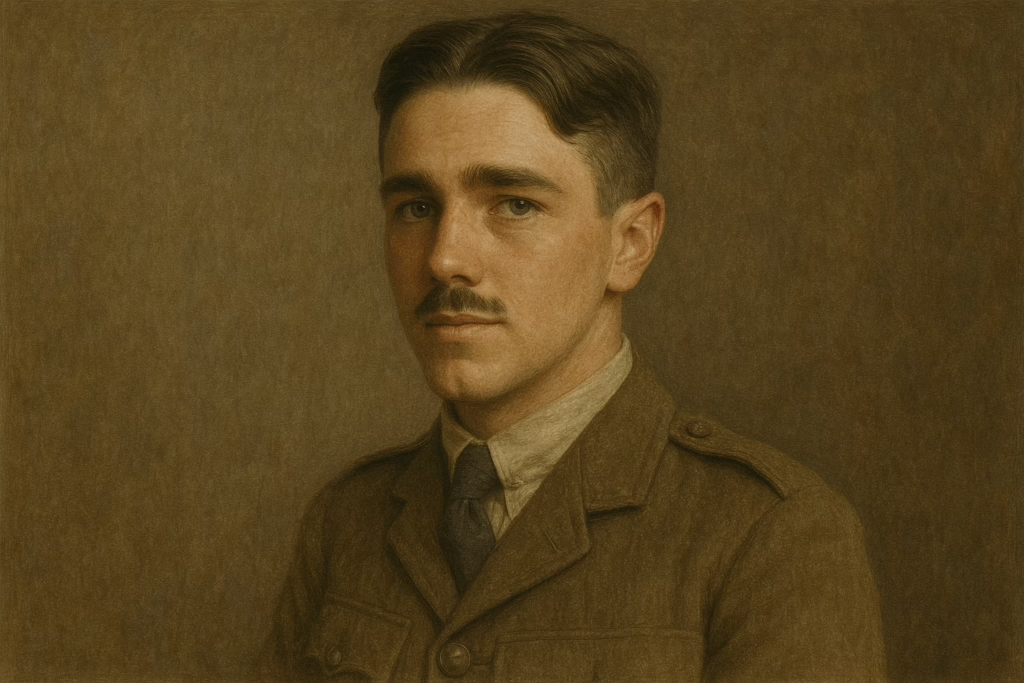

- Wilfred Owen (1893–1918)

- Representative works: “Dulce et Decorum Est,” “Anthem for Doomed Youth,” “Strange Meeting.”

- Significance: Owen’s powerful, image-laden, empathetic poems foreground the sensory reality of mechanised slaughter; his exploitation of assonance, pararhyme and shocking imagery revolutionised war verse.

- Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918)

- Representative works: “Break of Day in the Trenches,” “Dead Man’s Dump.”

- Significance: Rosenberg’s singular voice integrates Jewish identity, modern idiom and trench realism.

- Robert Graves (1895–1985) — war poems and later mythic studies; Good-Bye to All That (autobiography, 1929) is pivotal for inter-war memory.

- Other war poets of interest: Edward Thomas (killed 1917; lyric elegies), Charles Sorley (killed 1915), John McRae (Canadian but influential internationally). Note that many Georgian poets and younger lyricists wrote both pastoral and war poems; the war often transformed their poetic agendas.

C. Modernist and transitional poets (working within/against Georgian fields)

- T. S. Eliot (1888–1965) — The Waste Land (1922), The Hollow Men (1925), essays and critical works. Eliot’s dense, allusive, fragmentary lyric marks a radical break from Georgian accessibility and presses poetic form into modernist collage.

- W. B. Yeats (1865–1939) — though Irish, Yeats’s poetry (e.g. The Tower, 1928; The Winding Stair, 1929) is central to British literary life and reshapes lyric politics and mythic modernism.

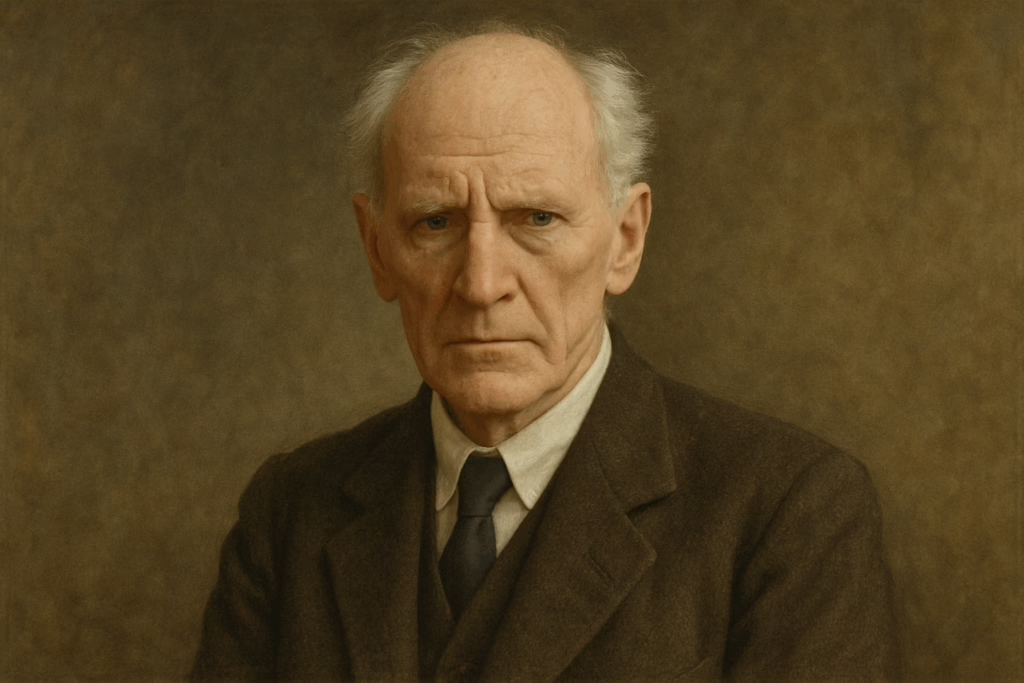

- A. E. Housman (1859–1936) — though his major collection (A Shropshire Lad, 1896) pre-dates the Georgian years, his spare, elegiac lyric remained influential across 1910–1936.

4.2 Novelists, short-story writers and memoirists

A. War and post-war memoirs, novels and social chronicles

- Ernest Hemingway (American; outside scope except for comparative note) — The impact of the war on prose style is widely international.

- Robert Graves — Good-Bye to All That (1929), an indispensable autobiographical account of war, social disillusion and the renegotiation of values.

- Siegfried Sassoon — aside from poetry, Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1930) is part of a wartime autobiographical trilogy.

- Ford Madox Ford (1873–1939)

- Representative works: The Good Soldier (1915) — an influential modernist novel using an unreliable narrator to explore adultery, deception and social decline.

- Significance: Ford’s narrative fragmentation and ironic distancing helped inaugurate new prose techniques.

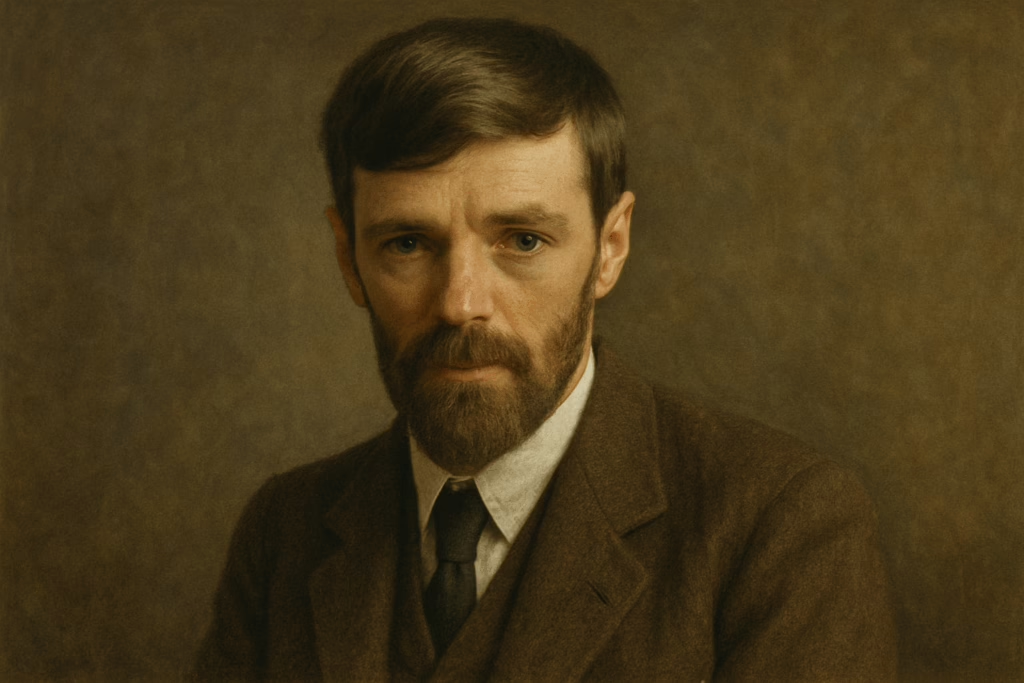

- D. H. Lawrence (1885–1930)

- Representative works: Sons and Lovers (1913), Women in Love (1920).

- Significance: Lawrence explored psychological realism, sexual conflict and the tensions between industrial modernity and instinctive life. His style and content provoked controversy.

- E. M. Forster (1879–1970)

- Representative works: A Room with a View (1908), Howards End (1910), A Passage to India (1924).

- Significance: Forster’s novels probe class, connection, and the moral necessity of human empathy; A Passage to India extended those themes to imperial contexts.

- Virginia Woolf (1882–1941)

- Representative works (within timeframe): Jacob’s Room (1922), Mrs Dalloway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927) — modernist experiments in stream of consciousness and temporality.

- Significance: Woolf’s narratives displace conventional plot in favour of psychological flux and social portraiture; Jacob’s Room (1922) marks a move toward fractured subjectivity.

- Aldous Huxley (1894–1963)

- Representative works: Crome Yellow (1921), Point Counter Point (1928) — satirical novels probing modern social and intellectual life.

- Katherine Mansfield (1888–1923)

- Representative works: Short stories such as “Bliss,” “The Garden Party” — flash fiction using impressionistic technique and concentrated psychological observation.

- Other novelists of note: John Galsworthy (continuing inter-war saga writing), Arnold Bennett (provincial novels), Robert Graves (also fiction), Compton Mackenzie, Naomi Mitchison (later).

B. Genre and popular fiction

- Arthur Conan Doyle — Detective fiction remained popular; late projects include The Lost World and other adventure tales.

- John Buchan — Escape and spy fiction, notably The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915) (just outside period but reflective of the genre’s growth).

- A. A. Milne — Children’s literature became a major feature of inter-war culture (see below under children’s literature).

4.3 Drama and theatre

- Noël Coward (1899–1973) — though his greatest successes lie slightly later, Coward began writing plays in the 1920s and contributed to a cosmopolitan, urbane theatre.

- George Bernard Shaw — his dramatic career spans into the Georgian years with plays interrogating social institutions.

- Irish and British theatre: The Abbey Theatre (founded 1904) and the broader revival of dramatic art provided spaces for nationalist and realist drama; writers like Lady Gregory and J. M. Synge (Irish) were influential across Britain.

4.4 Children’s literature

- A. A. Milne (1882–1956) — When We Were Very Young (1924), Winnie-the-Pooh (1926).

- Significance: Milne’s gentle, nostalgic verse and stories reflect inter-war longing for safety and childhood innocence; children’s literature became a significant cultural industry.

4.5 Essayists, critics and cultural commentators

- T. S. Eliot — critical prose (Tradition and the Individual Talent, 1919) shaped modernist theory.

- Virginia Woolf — essays (Modern Fiction, 1919; A Room of One’s Own, 1929) advanced feminist and aesthetic concerns.

- F. R. Leavis (later) and other critics initiated the serious study of modern English literature in university curricula.

5. Short summaries of major works (close-reading entry points)

Below are concise critical summaries of selected key works that anchor the Georgian Age and its borders with modernism. Each summary highlights structural features and interpretive directions suitable for advanced seminars.

5.1 The Good Soldier (Ford Madox Ford, 1915)

- Overview: The novel uses an unreliable first-person narrator (John Dowell) who recounts the tragic unravelling of two couples in pre-war Europe. It unfolds non-chronologically; its famous opening line (“This is the saddest story I have ever heard”) primes readers for layered irony.

- Key issues: Narrative reliability and self-deception; social hypocrisy; sexual morality; modern narrative technique (fragmentation and retrospective perspective).

- Seminar prompt: How does Dowell’s limited knowledge and self-presentation shape the reader’s judgements? Consider Ford’s experiments with time and the ethics of storytelling.

5.2 Dulce et Decorum Est; Anthem for Doomed Youth (Wilfred Owen)

- Overview: Owen’s poems juxtapose classical allusion and the bitter reality of the trenches; he uses vivid sensory detail, irony and unusual metrical patterns to portray the soldier’s suffering.

- Key issues: The indictment of jingoism; the moral responsibility of poets; techniques of shocking realism in lyric.

- Seminar prompt: Compare Owen’s sonic strategies (pararhyme, slant rhyme) with Georgian pastoral diction: how do formal choices produce ethical effects?

5.3 Mrs Dalloway (Virginia Woolf, 1925)

- Overview: A single-day novel that interweaves the interior consciousnesses of Clarissa Dalloway and other characters, including Septimus Warren Smith (a shell-shocked veteran). Woolf’s free indirect style, rhythmic prose and leaping focalisation compose a modernist portrait of post-war Britain.

- Key issues: Memory and temporality; the problem of representing trauma; urban sociology and private emotion; narrative technique (stream of consciousness).

- Seminar prompt: Read the parallel plotlines of Clarissa and Septimus as cultural commentaries on post-war Britain. How does Woolf’s narrative form enable empathy?

5.4 The Waste Land (T. S. Eliot, 1922)

- Overview: A fragmented, allusive poem that collages mythic, liturgical and contemporary elements to depict cultural desolation after the war. Its epigraphs, multilingual quotations and abrupt shifts demand intertextual reading.

- Key issues: Myth as structural device; urban desolation; the poet’s authority and tradition; the poem’s controversial reception and its role in defining modernist aesthetics.

- Seminar prompt: What role does myth (e.g. the Fisher King) play in organising Eliot’s poem? Compare the poem’s urban wasteland with Georgian pastoral aims.

5.5 Howards End (E. M. Forster, 1910)

- Overview: A social realist novel that maps class tensions, cultural ideals and the ethical claim to human connection. The house Howards End stands as an emblem for moral rootedness and the human desire to “connect.”

- Key issues: Property and human relationship; ethical pluralism; narrative irony and interpretive voice.

- Seminar prompt: Analyse Forster’s narrative strategies as moral argument. How does he use character types to stage broader social theses?

6. Principal themes, motifs and aesthetic developments

The Georgian Age (1910–1936) is best understood by examining recurrent thematic threads and the ways form responds to historical pressure.

6.1 Nature, nostalgia and pastoral retreat

- Continuity: Georgian poets often write in an accessible pastoral idiom that values nature as solace and refuge.

- Transformation: War trauma complicates pastoralism: nature becomes a site of mourning and elegy rather than simple idyll.

6.2 War, trauma and the ethics of memory

- Feature: The First World War reshapes poetic diction and subject matter; many poets adopt shock tactics to convey horror. Memoir, testimony and elegy become central literary modes.

6.3 Modernist experiment and narrative innovation

- Feature: The period sees the consolidation of modernist strategies — fragment, montage, free indirect discourse, stream of consciousness — shaped by psychological and aesthetic concerns about representation.

6.4 The politics of the domestic and the “private public”

- Feature: Many novels interrogate domestic spaces (homes, households) as microcosms of social change (class, gender, property). Forster’s “Only connect” is a famous articulation of an ethics of intimacy in a fragmented public domain.

6.5 Empire and cultural boundary-making

- Feature: The entanglements of imperial power appear in fiction and poetry as questions of identity, guilt and cultural contact. Conrad’s critiques and Forster’s ambivalence about empire are central frames of reference.

6.6 Gender, the New Woman and changing subjectivities

- Feature: Women’s writing and male portrayals of female subjectivity expand; the New Woman figure produces tensions that novels and plays address in different, often contradictory, ways.

7. Forms and formal techniques: how the Georgian Age reconfigured style

7.1 Poetry

- Georgian lyric generally uses direct diction, shorter forms and calm musicality; war poets employed harsher acoustic patterns, dissonance and dramatic imagery. Modernist poets like Eliot and Pound deployed collage, fragment and irregular prosody.

7.2 Prose and the novel

- The novel becomes pluralised: realist panoramas continue (Galsworthy, Bennett), while fragmented, unreliable narrators and psychological novels (Ford, Woolf, Lawrence) reshape narrative authority. Serialization remains influential, but book-form and experimental journals foster innovation.

7.3 Drama and performance

- Playwrights combine social pedagogy and entertainment; modern drama experiments with stagecraft, symbol and didacticism.

7.4 Periodical culture and the little magazine

- Little magazines and reviews (the Egoist, The New Age, The Criterion) become crucial forums for new forms. They allowed modernists to publish pieces that would have been commercially risky in mainstream outlets.

8. Critical approaches and interpretive frameworks (for advanced study)

The Georgian Age invites multiple critical lenses:

- New Historicism / Cultural Materialism: Read texts in relation to wartime economies, class formation, and public discourse.

- Trauma Studies: Apply approaches that address representation of catastrophic experience and the limits of language in war poetry.

- Gender Studies & Feminist Criticism: Focus on the New Woman, domestic conflict, authorial gender positions and the gendering of modern subjectivity.

- Post-colonial Perspectives: Analyse imperial narratives and constructions of the colonised (Conrad, Forster) and interrogate racial discourses.

- Formalist / Modernist Theory: Investigate how modernist techniques restructure time, voice and intertextuality.

9. Suggested seminar modules and graduate research projects

Seminar clusters

- “Pastoral and Burial: Georgian Poets and the First World War.” Read Edward Marsh’s selections alongside Owen, Sassoon, Brooke and Rosenberg.

- “Modernist Breaks: Woolf, Eliot and the Georgians.” Examine tensions between pastoral lyric and poetic collage.

- “Narrative Unreliability and the Ethics of Storytelling.” Focus on The Good Soldier, Howards End, Mrs Dalloway and Jacob’s Room.

- “Empire and Its Discontents.” Read Conrad, Forster (A Passage to India), and imperialist fiction to address cultural encounter and ethical ambiguity.

Graduate research topics

- “The serial novel and modernist temporality: how instalment publication shaped narrative form (1910–1936).”

- “Trauma, elegy and the memorial aesthetic: representations of the war dead in Georgian and modernist poetry.”

- “The ‘New Woman’ in British fiction, 1910–1936: social reality and literary figure.”

- “Georgian pastoral vs. modernist fragment: competing visions of British identity in the inter-war years.”

10. Annotated bibliography and primary editions

Primary texts (recommended editions)

- Marsh, Edward (ed.), Georgian Poetry (Volumes, 1912–1922) — for primary anthologies.

- Owen, Wilfred, Poems (Selected editions; see published Owen collected poems edited by Jon Stallworthy or similar).

- Sassoon, Siegfried, The War Poems (various collected editions).

- Ford, Ford Madox, The Good Soldier (Penguin/Everyman).

- Woolf, Virginia, Mrs Dalloway and To the Lighthouse (Penguin/Norton Critical Editions).

- Eliot, T. S., The Waste Land (Faber & Faber; Norton Critical Editions include essays and context).

- Forster, E. M., Howards End (Penguin/Norton).

- Masefield, John, Selected Poems (Penguin).

- Brooke, Rupert, Collected Poems (various scholarly editions).

Secondary scholarship (study and reference)

- Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory — seminal for war literature and memory (essential reading).

- Jon Stallworthy, Wilfred Owen — a thorough biography and critical account.

- R. M. Gardner, Georgian Poetry: An Anthology and Critique — study of the movement (expository).

- Susan Sontag and other modernist critics for formalist studies (selected essays).

- Peter Howarth and John M. McAuliffe, eds., The Cambridge Companion series on modernist and war literature (consult specific volumes on Forster, Woolf, Eliot).

- For modern archival work, consult scholarly editions (Oxford, Cambridge / Norton) and author biographies.

11. Exam questions and discussion prompts (advanced level)

- “Discuss the poetic responses to the First World War. How does form contribute to the ethical messaging of Owen and Sassoon?”

- “Compare the pastoral aims of the Georgian poets with the aesthetics of modernism. What do the differences tell us about cultural responses to modernity?”

- “Analyse the role of the unreliable narrator in The Good Soldier and Mrs Dalloway. What ethical responsibilities do narrators bear in accounting for others?”

- “Examine how Howards End stages the relationship between property and human connection.”

- “Trace the impact of serialisation on narrative technique in a pair of novels published in instalments between 1910 and 1930.”

12. Concluding remarks

The Georgian Age (1910–1936) is not a single, coherent movement but a lively historical field in which traditional pastoral lyric, war testimony, social realism and avant-garde modernism coexist, collide and cross-pollinate. Its literary significance resides in the moment of transition it marks: the last great expression of accessible lyricism and narrative social realism gives way to experimental forms that will dominate much of twentieth-century literature. For higher-study students, the period rewards approaches that combine close textual analysis with historical contextualisation — particularly in relation to the cataclysm of 1914–18 and its cultural after-effects.