The Neoclassical Period in English literature (commonly dated 1660–1798) is a long, multifaceted age that follows the turbulent years of the English Civil Wars and the closing of the Renaissance, and precedes the full rise of Romanticism. It is commonly divided into three broad sub-periods—the Restoration (1660–1700), the Augustan Age (c. 1700–1745), and the Age of Sensibility / Pre-Romantic period (c. 1745–1798)—each with its own dominant concerns, genres, and stylistic norms.

Neoclassicism prized reason, decorum, order, proportion, and the imitation of classical models (Greek and Roman). Writers emphasized clarity, restraint, balance, and wit. At the same time, the period witnessed seismic social, political, scientific, and economic shifts—restoration of the monarchy, the Glorious Revolution, the rise of the public sphere, the growth of print culture, the scientific revolution and empiricism, and the early stirrings of industrial and imperial expansion. These forces shaped the literature: satire and political pamphleteering flourished; the novel emerged as a major genre; periodicals and essays formed a new public literary culture; and drama moved from libertine comedy toward greater moral seriousness.

This chapter maps the period historically and intellectually, describes its characteristic forms and aesthetics, discusses its principal subdivisions in detail, lists major authors categorically, and offers concise summaries of the central works students should know.

Historical Background & Major Events (and Their Literary Impacts) in the Neoclassical Period

1. Restoration of the Monarchy (1660)

- Event: Charles II returned to the throne after the Interregnum (Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth).

- Impact on literature: The reopening of the theatres; a dramatic revival—restoration drama (notably, the comedy of manners) flourished. Satire and courtly literature re-emerged; writers who had been silenced or exiled found patronage. The climate encouraged urban, witty, libertine writing reflective of court culture.

2. The Great Plague (1665) and the Great Fire of London (1666)

- Impact: Both events altered urban life and stirred reflections on mortality, urban vulnerability, and social order. The fire accelerated rebuilding, and the aftermath fed into pamphlet literature, sermons, and moral reflection.

3. The Glorious Revolution (1688) and the Bill of Rights (1689)

- Event: William III and Mary II replaced James II; the constitutional monarchy was strengthened.

- Impact: Stimulated political writing and a culture of pamphleteering and satire. Political allegory and satire (e.g., Dryden’s and later Pope’s works) responded to party politics (Tories vs Whigs). The revolution helped create conditions for a freer (though contested) public sphere.

4. The Rise of the Public Sphere, Coffeehouses, and the Print Culture

- Impact: Expansion of literacy, lower printing costs, and periodicals (e.g., Tatler, Spectator) created a reading public—urban, commercial, and politically engaged. Coffeehouses became places of debate and literary sociability; magazines and journals shaped taste and manners, and they helped standardize language and literary forms.

5. The Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment

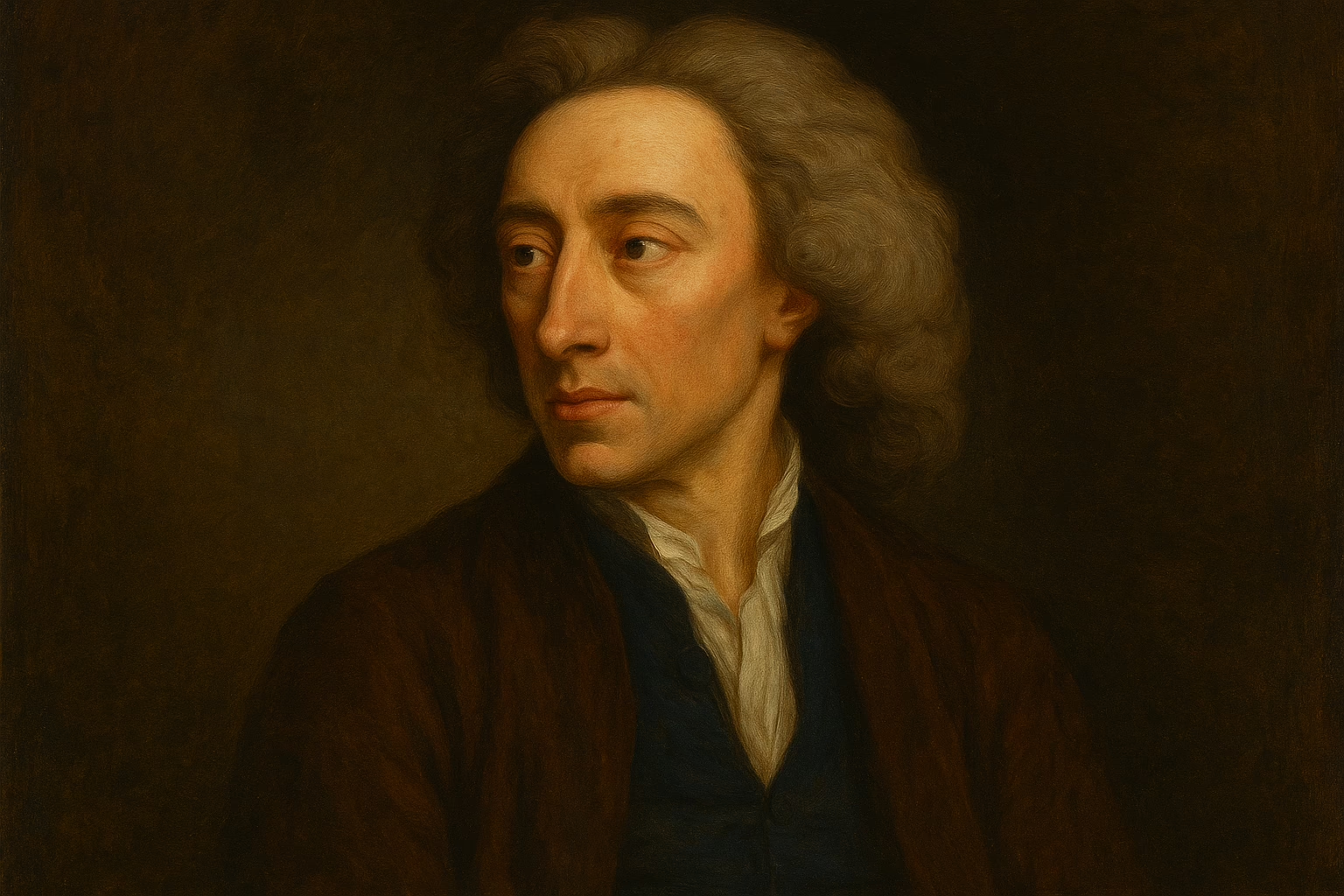

- Events/figures: Isaac Newton (Principia, 1687), John Locke (Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 1690).

- Impact: Emphasis on reason, observation, and empiricism influenced literary aesthetics: clarity, order, and argument became prized. Political and philosophical discourse matured, shaping essays, satire, and didactic literature.

6. The Act of Union (1707)

- Event: Union between England and Scotland formed Great Britain.

- Impact: A political and cultural reconfiguration that affected literary patronage, national identity, and the circulation of texts across Britain.

7. The Licensing Act (1737)

- Event: Government regulation of the stage and theatrical censorship (requirement of licensing for plays).

- Impact: Curtailed political satire on stage; shifted some critical energy into the essay, pamphlet, and novel. Theaters adapted with less overt political drama and more emphasis on moral or sentimental plays.

8. Colonial Expansion and the Early British Empire

- Impact: Contact with other cultures, economic growth, and an expanding mercantile class shaped themes of commerce, travel, and national identity in literature.

9. The American (1776) and French Revolutions (1789 onward)

- Impact: Toward the late 18th century, revolutionary ideas triggered passionate political writing, philosophical reflection, and polarization. Edmund Burke and Mary Wollstonecraft directly responded to these events with major political treatises; the atmosphere helped provoke Romanticism’s emotional revolt against Neoclassical restraint.

Aesthetic Principles & Literary Characteristics

- Imitation of Classical Models: Emphasis on rules derived from Aristotle and Horace—unity, decorum, verisimilitude.

- Reason and Order: Literature valued rationality, balance, and clear argument.

- Wit and Satire: Intellectual playfulness and moral critique through irony and satire (e.g., Pope, Swift).

- Formality and Politeness: Style reflected social hierarchies and decorum, especially in courtly genres.

- Heroic Couplet: The dominant poetic form (closed couplets in iambic pentameter), perfected by Dryden and Pope.

- Didacticism: A tendency toward moral instruction and social criticism.

- Rise of Prose Forms: Essays, periodicals, criticism, political pamphlets, and the novel.

- Genre Evolution: Restoration comedy → Augustan satire → sentimental and moral drama → the novel (epistolary and picaresque/realistic forms).

Subdivisions — Detailed Treatment

A. The Restoration (1660–1700)

Context & Character:

- A courtly and often libertine culture. Theatres reopened (after Puritan suppression). Restoration drama includes both comedy of manners and heroic drama.

- Notable cultural feature: the emergence of professional female actors and women playwrights (e.g., Aphra Behn).

Major Genres & Authors:

- Drama (Comedy of Manners): William Wycherley (The Country Wife), William Congreve (The Way of the World), George Etherege (The Man of Mode).

Characteristics: urban settings, satire of social mores, sexual frankness, witty dialogue, and emphasis on fashions and affectations of the elite. - Heroic Drama / Tragedy: John Dryden wrote heroic tragedies (e.g., All for Love).

- Poetry & Satire: John Dryden — dominant poet, critic, and dramatist. He established the heroic couplet as a strong vehicle for satire and public commentary.

- Prose & Political Writing: The period saw political pamphlets and essays responding to the Restoration settlement and subsequent political conflicts.

Literary Impact:

- The Restoration established theatre as a central public art form, but its libertinism provoked a moralist backlash that would shape later sentimental drama.

- Dryden’s theoretical writings (e.g., An Essay of Dramatic Poesy) helped codify literary criticism and neoclassical taste.

B. The Augustan Age (c. 1700–1745)

Context & Character:

- Often considered the high point of English neoclassicism; writers deliberately modeled themselves on Augustan Rome—hence the name.

- Political life was dominated by party politics (Whigs vs Tories), and satire became an instrument of both aesthetic and political critique.

Major Genres & Authors:

- Satirical Poetry & Essay: Alexander Pope (the supreme neoclassical poet), Jonathan Swift (satirist of human folly), John Gay (satiric dramatist), Samuel Johnson (later in the period but key).

- Periodical Essay & Criticism: Richard Steele and Joseph Addison (journals Tatler, Spectator) established the periodical essay, shaping public taste, etiquette, and moral instruction.

- Prose Satire & Political Pamphlets: Swift’s A Modest Proposal and Gulliver’s Travels; political pamphlets addressed the pressing public questions.

- The Novel Emerges: Early forms include Daniel Defoe (journalistic fiction like Robinson Crusoe), and later Richardson and Fielding reform and expand the novel.

Aesthetics & Innovations:

- Mastery of the heroic couplet (Pope) for polished, epigrammatic expression.

- Satire becomes the defining mode—formal, ironic, often moralizing.

- Development of a public taste mediated by periodicals, which taught civility, sociability, and critical standards.

Social Function:

- Literature became an instrument in shaping and critiquing English public life—taste, manners, politics, and commercial culture.

C. The Age of Sensibility / Pre-Romantic Period (c. 1745–1798)

Context & Character:

- A gradual shift away from strict neoclassical rationalism toward feeling, sentiment, and subjective experience. The term “Age of Sensibility” captures the heightened emphasis on sensibility and emotion—especially in essays, poetry, and the novel.

- This phase witnesses the maturation of the novel, the rise of the graveyard poets (meditative and melancholy verse), and the development of sentimental drama. It culminates in the late-century political ferment (French Revolution) that contrasts with burgher literary tastes.

Major Genres & Authors:

- The Novel: Samuel Richardson (epistolary novel), Henry Fielding (comic realism), Laurence Sterne (Tristram Shandy experimental narrative), Tobias Smollett (picaresque), Fanny Burney (social novels), Oliver Goldsmith (The Vicar of Wakefield).

- Poetry: Thomas Gray (“Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”), William Collins, Edward Young (Night Thoughts), and Robert Burns (folk-inspired lyric poetry) — all prefigure Romantic sensibility.

- Political & Philosophical Prose: Edmund Burke (Reflections on the Revolution in France), Mary Wollstonecraft (A Vindication of the Rights of Woman), and the continuing relevance of Locke and Newtonian thought.

- Drama: Shift from Restoration libertinism to sentimental comedies and social comedies; Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The Rivals and The School for Scandal (satirical comedies of manners with moral subtext).

Aesthetics & Innovations:

- Novels foreground individual feeling, moral dilemmas, and the domestic sphere; they increasingly address middle-class readers.

- Emotive poetry, melancholy, and pre-Romantic nature appreciation grow; poets experiment with lyric immediacy and meditative modes.

- Literatures of sensibility (essays, letters, conduct books) promote empathy and moral refinement.

Major Authors & Their Works — Categorical Listing (with brief descriptions)

Poets, dramatists, novelists, essayists, critics and political writers are grouped for clarity. After each author I list principal works and then short summaries are provided in the next section.

Poets & Satirists

- John Dryden — Annus Mirabilis, Absalom and Achitophel (1681), Mac Flecknoe (1682), All for Love (1678), An Essay of Dramatic Poesy (1668).

- Alexander Pope — Essay on Criticism (1711), The Rape of the Lock (1712/1714), An Essay on Man (1733–34), translations of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.

- Jonathan Swift — Gulliver’s Travels (1726), A Modest Proposal (1729), A Tale of a Tub.

- Thomas Gray — Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1751), Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat.

- William Collins, Edward Young — (e.g., Night Thoughts).

- Robert Burns — Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (1786).

Dramatists

- Aphra Behn — The Rover (1677), one of the first professional female playwrights.

- William Wycherley — The Country Wife (1675).

- William Congreve — The Way of the World (1700).

- George Etherege — The Man of Mode (1676).

- John Dryden — All for Love (a reworking of Antony and Cleopatra).

- Richard Brinsley Sheridan — The Rivals (1775), The School for Scandal (1777).

Essayists, Critics & Periodical Writers

- Joseph Addison & Richard Steele — Tatler (1709–1711), Spectator (1711–1712) — essays on manners and morality.

- Samuel Johnson — A Dictionary of the English Language (1755), Lives of the Poets (1779–81), essays and criticism.

- Francis Bacon (earlier, but influential): Essays (reused as a touchstone for later prose).

- Edmund Burke — A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757); Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790).

- Mary Wollstonecraft — A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792).

Novelists & Fiction Writers

- Daniel Defoe — Robinson Crusoe (1719), Moll Flanders (1722).

- Samuel Richardson — Pamela (1740), Clarissa (1748), Sir Charles Grandison (1753).

- Henry Fielding — Joseph Andrews (1742), Tom Jones (1749).

- Laurence Sterne — The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759–1767).

- Tobias Smollett — The Adventures of Roderick Random (1748), Humphry Clinker (1771).

- Fanny Burney — Evelina (1778), Cecilia (1782).

- Oliver Goldsmith — The Vicar of Wakefield (1766).

Political Philosophers & Social Thinkers

- John Locke — Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690).

- Thomas Hobbes (earlier; influence), Edmund Burke, Mary Wollstonecraft — political and moral writing shaped public debates.

Short Summaries of Major Works (Focused & Accessible for Higher Studies)

Poetry, Satire & Critical Works

John Dryden — Absalom and Achitophel (1681)

A political allegory using biblical exempla to comment on the Exclusion Crisis. Dryden satirizes political figures in thinly veiled portraits; the poem is an excellent example of the heroic couplet used for public political satire.

John Dryden — Mac Flecknoe (1682)

A satire mocking the poet Thomas Shadwell, cast as the heir to the kingdom of dullness. It showcases Dryden’s mastery of mock-epic and invective.

Alexander Pope — Essay on Criticism (1711)

A poetical didactic essay advising critics and poets on rules of taste: balance between nature and art, following rules, and the proper use of judgment and judgment’s limits.

Alexander Pope — The Rape of the Lock (1712/1714)

A mock-epic that lampoons high society’s foibles through a trivial incident (the cutting of a lock of hair). It blends wit with a moralizing undercurrent, using the machinery of epic to satirize fashionable vanity.

Alexander Pope — An Essay on Man (1733–34)

A philosophical poem in heroic couplets that attempts to “vindicate the ways of God to man,” arguing for a rational order and the limited capacity of human understanding.

Jonathan Swift — A Modest Proposal (1729)

An ironical, savage satirical pamphlet suggesting the eating of Irish children as a solution to poverty—an extreme example of satiric misanthropy meant to shame English policy toward Ireland.

Jonathan Swift — Gulliver’s Travels (1726)

A prose satire in travel narrative form that skewers human folly, political corruption, and the pretensions of science and learning through imaginary voyages to Lilliput, Brobdingnag, Laputa, and the land of the Houyhnhnms.

Thomas Gray — Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1751)

A meditative lyric that reflects on mortality, the dignity of humble lives, and the universalizing power of death. It anticipates Romantic concerns with rural life and individual sentiment.

Drama

Aphra Behn — The Rover (1677)

A comic, adventurous, and sexually candid play reflecting Restoration attitudes about gender, power, and sexual politics. Behn’s status as one of the first professional women writers is historically vital.

William Wycherley — The Country Wife (1675)

A bawdy comedy of manners that satirizes hypocrisy and sexual morality of Restoration society.

William Congreve — The Way of the World (1700)

A sophisticated comedy exploring marriage, money, and manners; admired for its subtlety, verbal dexterity, and complex plot.

Richard Brinsley Sheridan — The School for Scandal (1777)

A later neoclassical comedy that satirizes gossip and hypocrisy in polite society; it shows the line from Restoration comedy to more moralized 18th-century drama.

The Novel

Daniel Defoe — Robinson Crusoe (1719)

Presented as a true account, it is a survival tale and a meditation on providence, commerce, and colonial enterprise. It helped define the novel as a genre grounded in individual experience and realistic detail.

Samuel Richardson — Pamela (1740)

An epistolary novel about a servant girl’s resistance to her master’s advances; it explores virtue, social mobility, and domestic morality. It sparked debates about fiction and character (and provoked Fielding’s satire).

Samuel Richardson — Clarissa (1748)

A monumental epistolary tragedy of sexual violence and familial tyranny; it probes inner psychology, moral complexity, and the limits of social virtue.

Henry Fielding — Tom Jones (1749)

A picaresque, comic epic of a foundling’s adventures; balances moral seriousness with broad comic situations; a formative novel of realism and panoramic social representation.

Laurence Sterne — Tristram Shandy (1759–67)

An experimental, digressive novel that plays with narrative form, authorial voice, and the instability of meaning; it prefigures modernist narrative anxieties.

Fanny Burney — Evelina (1778)

A novel of manners that addresses female socialization, reputation, and the novel’s growing preoccupation with middle-class domestic concerns.

Oliver Goldsmith — The Vicar of Wakefield (1766)

A sentimental and humane novel about rural life, Christian charity, and human resilience; it influenced the development of the novel’s moral imagination.

Prose, Philosophy & Political Writing

John Locke — Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690)

A foundational empiricist work arguing that human knowledge derives from experience, shaping later Enlightenment and literary emphasis on observation and reason.

Edmund Burke — Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)

A polemical conservative critique of revolutionary radicalism that became a touchstone for debates about tradition and reform.

Mary Wollstonecraft — A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

A radical feminist argument for women’s education and rational equality, directly responding to Burke and the politics of the French Revolution.

Samuel Johnson — A Dictionary of the English Language (1755)

A monumental achievement in lexicography that helped stabilize spelling, usage, and the intellectual standards of the language.

Themes and Intellectual Currents

- Order vs. Disorder: Poets and satirists sought to restore moral and aesthetic order by ridiculing vice and folly.

- Reason vs. Passion: An ongoing tension between rational order (neoclassicism) and emergent sensibility and emotion (pre-Romantic).

- Public Sphere & Sociability: The rise of periodicals and coffeehouses created a public culture of criticism, taste-making, and debate.

- Politics & Satire: Writers engaged directly with party politics and public policy through satire and pamphlet literature.

- Moral Didacticism: Literature frequently had instructive aims—on manners, virtue, domestic conduct, and nationalism.

- Rise of Individual Subjectivity: The novel and some lyric poetry foreground interior life and conscience, anticipating Romantic introspection.

Institutions, Markets & Social Context

- Patronage → Market: A gradual shift from aristocratic patronage to a market-driven literary economy. Authors increasingly wrote for a paying public.

- Print & Censorship: Printing expanded rapidly; the state attempted to control the press (e.g., Licensing Act) but the periodical press proved resilient.

- Gender & the Public: Women played a growing role—as readers, moral authorities, novelists, and critics (e.g., Aphra Behn, Fanny Burney, Mary Wollstonecraft).

- Urbanization & the Middle Class: A growing urban middle class read novels and periodicals; literature addressed their tastes and anxieties.

The Neoclassical Legacy and Transition to Romanticism

- Stability of Form: The period codified forms (heroic couplet, satire, the essay) and codified critical standards that dominated the 18th century.

- Seeds of Romanticism: The graveyard poets’ preoccupation with mortality, the novel’s concern with individual feeling, and the critique of mechanistic reason laid the groundwork for Romantic aesthetics. By the 1790s, the revolutionary ethos and a renewed emphasis on feeling, imagination, and nature culminated in Romanticism’s break with neoclassical orthodoxy.

Annotated Bibliography & Suggested Readings (for further study)

- Primary Texts (recommended editions):

- Dryden, Selected Poetry and Prose (Oxford World’s Classics).

- Pope, The Major Works (Oxford World’s Classics).

- Swift, Gulliver’s Travels and Other Writings (Penguin Classics).

- Richardson, Pamela and Clarissa (Norton Critical Editions).

- Fielding, Tom Jones (Penguin Classics).

- Sterne, Tristram Shandy (Penguin Classics).

- Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language (selections) and Lives of the Poets.

- Goldsmith, The Vicar of Wakefield (Oxford World’s Classics).

- Burney, Evelina (Oxford World’s Classics).

- Secondary Reading:

- Paulson, Ronald, The Life of Alexander Pope.

- Butler, Martin (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to English Literature, 1660–1780.

- Habermas, Jürgen, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (for theoretical context on periodicals and coffeehouses).

- Ferguson, Frances, Pornography, The Theory (for discussions of gender and sexuality in 18th-century print culture).

- Sabor, Peter (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to English Literature, 1740–1830.

Conclusion

The Neoclassical period (1660–1798) is a rich, culturally dynamic era in which literature served as both an instrument of social order and a laboratory of new literary forms. It consolidated critical standards, perfected satire and polished poetic diction, pioneered the essay and periodical culture, and birthed the modern novel. Politically engaged and culturally public, it reflects the transition from court-centered patronage to a market-oriented literary public. Its tensions—between reason and feeling, decorum and experiment, public satire and private sentiment—make it a complex and productive field of study. For higher studies, this period offers not only canonical masterpieces but also crucial insights into the transformation of literature’s social role and form on the eve of Romanticism.