Preface — how this chapter approaches “postmodern”

“Postmodern” is a capacious, contested label that names a set of historical conditions, intellectual questions and formal techniques that became salient after the Second World War. This chapter treats the Postmodern Age (c. 1945–present) as a long phase in which literature responds to (1) the collapse or discrediting of grand metanarratives (national progress, teleological history, unitary humanism), (2) technological transformations and mass culture, (3) the breakdown and reconfiguration of empire, and (4) a set of aesthetic experiments — metafiction, pastiche, intertextuality, and pronounced self-reflexivity — that question language’s capacity to represent a stable world. Many literary theorists and handbooks summarise postmodern literature in these terms: it foregrounds parody, irony, fragmentation, and a play of signs that refracts historical and political anxieties into form. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Important note on method: “Postmodern” is not a single agreed school. It overlaps with (and in places follows) modernism; some writers labeled “postmodern” are continuers of modernist experiments, some are reactionary toward them, and others mix political engagement with self-reflexive form. This chapter therefore treats the period historically (events and conjunctures) and formally (techniques and genres), and it offers generous reading routes rather than rigid taxonomies.

I. Historical map (major events 1945–present) and their literary impacts

The literature of the postwar world responds to a set of epochal transformations. Below are the central historical nodes and the principal ways literature took them up.

1. The Second World War and its aftermath (1945–1950s)

Events: Total war, the Holocaust, atomic bombing, mass displacement, the start of the Cold War.

Literary impacts: Immediate postwar writing (memoir, reportage, documentary fiction) focuses on witnessing, trauma and ethical responsibility; the shock of mass annihilation made many writers suspicious of teleological narratives of progress and of language’s ability to “hold” experience, encouraging formal fragmentation and ethical self-consciousness. Novelists and poets experimented with non-chronological narratives, witness testimony, and new poetics that could convey discontinuity and moral perplexity.

2. Decolonisation and the end of empires (late 1940s–1970s)

Events: Indian independence (1947), independence across Africa and Asia, the dismantling of European empires.

Literary impacts: Postcolonial voices enter the anglophone literary field: writers from formerly colonised regions interrogate national narratives and hybrid identities. Their influential novels and theoretical interventions (e.g., postcolonial criticism) problematise Eurocentric conceptions of history, identity and language, and they frequently use postmodern techniques (self-reflexivity, mythic revision) to rework national pasts.

3. Cold War, nuclear threat and ideological polarisation (late 1940s–1989)

Events: Bipolar global order, proxy wars, authoritarian regimes, ideological propaganda.

Literary impacts: Political paranoia, satire, and dystopia flourish (e.g., dystopian allegories and speculative fictions), and writers use irony and black humour to interrogate mass-media culture, totalising ideologies, and the problem of truth in the information age.

4. Mass consumer culture, media expansion and information technologies (1950s–present)

Events: Television, later cable and satellite, the rise of advertising, then the Internet and social media.

Literary impacts: Postmodern texts often thematise simulation, media saturation, and the commodification of everyday life. Authors use pastiche and collage to mimic the multiplicity of mediated experience; theorists such as Baudrillard argued that the simulacrum replaces the real — a concept fiction-makers dramatise.

5. Civil rights movements, feminism, LGBTQ+ movements, decolonial struggles (1960s–present)

Events: US Civil Rights, global decolonisation, second-wave feminism, gay liberation, Black Power, indigenous movements.

Literary impacts: Diverse voices insist on re-writing and re-framing the canon. The post-1960s literary field becomes multiply plural: postcolonial novels, feminist fiction, queer writing, and minority literatures use hybrid forms and narrative strategies to destabilise received histories and to create new narrative practices.

6. Globalisation, migration and multiculturality (1980s–present)

Events: Transnational flows of people, capital and culture; acceleration of diasporic communities.

Literary impacts: “World literature” and transnational narratives become central. Authors from diasporic backgrounds blend linguistic registers and interweave local and global perspectives — often in formally adventurous ways (magical realism, non-linear histories, polyvocal narrators).

7. Digital revolution and the networked world (1990s–present)

Events: Internet, digital media, social platforms, datafication.

Literary impacts: New forms (hypertext fiction, electronic literature, experimental digital storytelling) appear; digital culture’s remix logic resonates with postmodern pastiche and has been argued to produce “post-postmodern” turns (e.g., metamodernism, digital modernity) — but many continuities remain.

For a concise definition and context of postmodernism and its literary teachings see reference handbooks: Britannica and Oxford Reference provide accessible summaries of postmodern tendencies in the arts and letters. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

II. Subdivisions of the Postmodern Age (heuristic)

Because the Postmodern Age covers many decades and divergent tendencies, useful analytical subdivisions are:

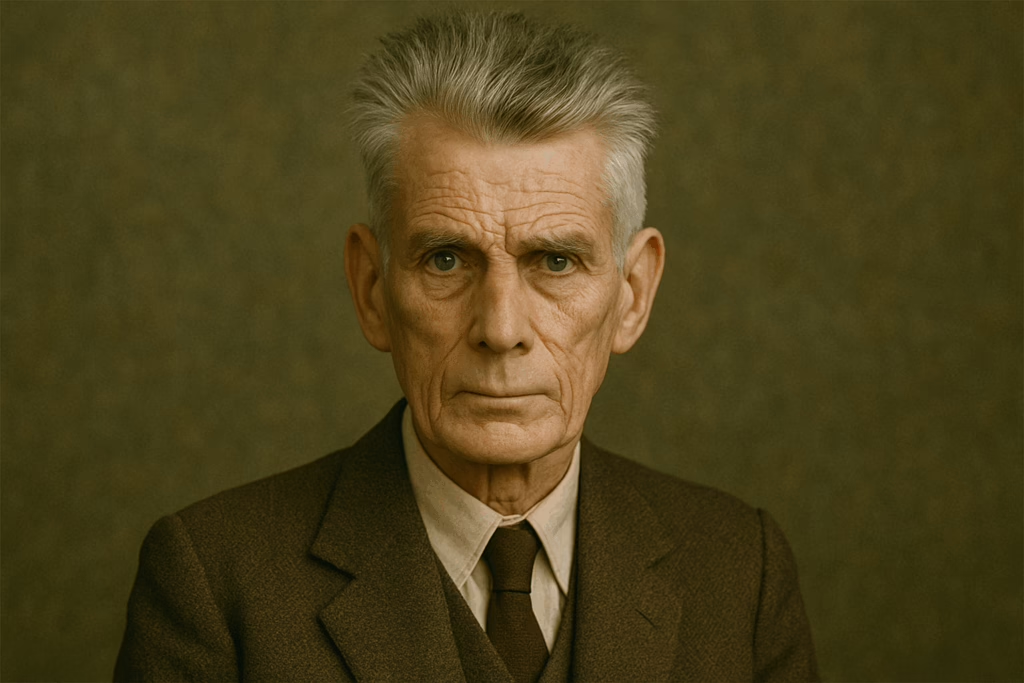

- Early/Postwar experimentalism (1945–1960). High modernist legacies remain; writers like Samuel Beckett and Jorge Luis Borges consolidate a self-reflexive, absurd and metafictional idiom; early Anglophone experiments appear (Nabokov’s late works, Beckett’s plays).

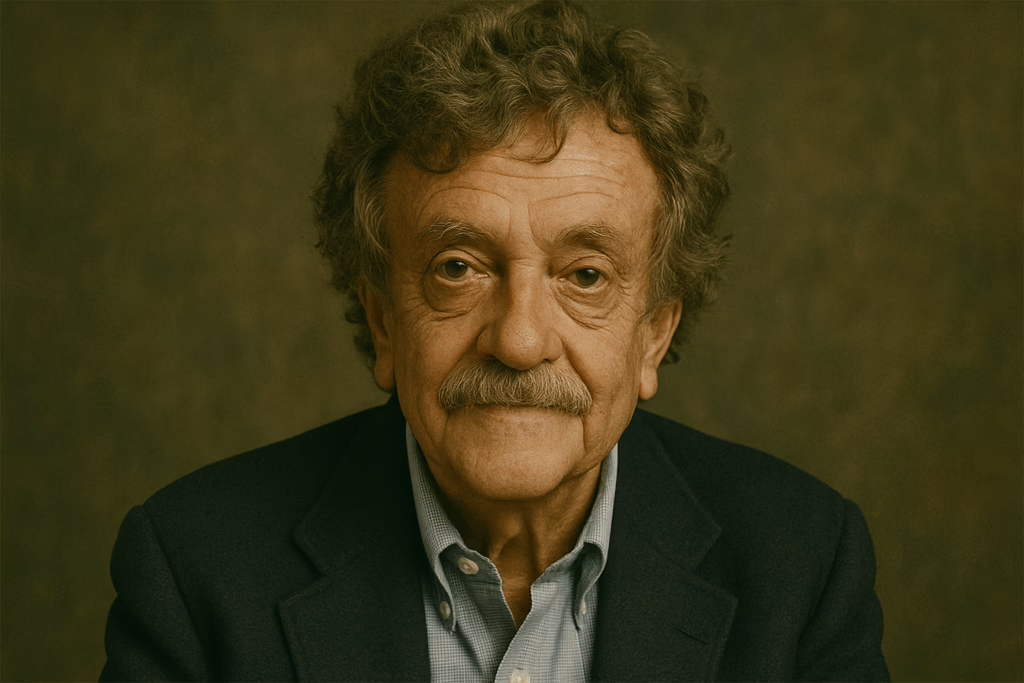

- Consolidation of postmodernist aesthetics (1960s–1980s). Metafiction, maximal novels, historiographic metafiction and pastiche flourish. Notable are John Barth, Thomas Pynchon, Italo Calvino, Kurt Vonnegut, and Donald Barthelme. This phase is also the era when postmodern theory (Lyotard, Derrida, Baudrillard, Foucault) becomes widely discussed in literary criticism. (MasterClass)

- Globalisation and postcolonial/postmodern convergences (1970s–1990s). The postcolonial novel and magic realism (Rushdie, Márquez) rewrite histories with hybrid forms; historiographic metafiction (Linda Hutcheon) addresses how history and fiction intertwine.

- Late/Post-postmodern and digital era (1990s–present). Genres hybridise further; some critics argue for “post-postmodern” or “metamodern” tendencies (a renewed search for sincerity and ethical engagement alongside self-reflexivity). Digital media and hypertext fiction complicate textual authority. (For a mapped timeline and list of key novels across decades see consolidated bibliographies and lists; an accessible list of canonical postmodern novels is available in public bibliographies and handbooks.) (Wikipedia)

III. Formal features & recurring techniques in postmodern literature

Although heterogenous, postmodern writing commonly uses a cluster of formal strategies (the list below is summarised from standard handbooks and literary surveys):

- Metafiction and self-reflexivity: the text calls attention to its own artifice, often commenting on storytelling itself (e.g., Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveller).

- Pastiche and intertextuality: multiple registers and styles are sampled and juxtaposed (e.g., Eco’s medieval detective mixed with semiotics).

- Irony, parody and black humour: a skeptical, often playful stance toward grand narratives.

- Historiographic metafiction: fictionalisation of history that highlights the constructedness of historical narratives (Linda Hutcheon’s term).

- Temporal play and fragmentation: non-linear time, montage, or narrative discontinuity.

- Unreliable narrators and polyvocality: multiple perspectives and narrators who are knowingly unreliable.

- Magical realism and mythic revision: especially in postcolonial contexts — blending of fantastic and realist modes (Márquez, Rushdie).

- Maximal and minimalist strategies: both extremely long, encyclopaedic novels (Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow) and short, aphoristic forms (Calvino’s fables) are part of the repertoire.

- Play with genre boundaries: crime, science fiction, memoir, and academic discourse are mixed (genre-blending is common). (Oxford Reference)

IV. Major authors and their representative works — categorical survey

Below I present a selective, research-focused catalogue of influential postmodern authors across regions and genres. Each entry lists major works and a short analytic description suitable for higher-study.

Selection logic: The list emphasises writers often taught or cited as central to postmodern literature across Anglophone and international traditions. It is necessarily selective — the field is vast and continually evolving.

A. Foundational precursors & early postwar experimentalists

Jorge Luis Borges (Argentina)

- Key works: Ficciones (1944, 1956), The Aleph (1949).

- Why read: Borges’s short fictions are canonical models of metafictional play: labyrinths, infinite texts, paradox and the problem of textual authority; his work prefigures later postmodern preoccupations with intertextuality and the ontology of the text.

Samuel Beckett (Ireland/France)

- Key works: Waiting for Godot (play, 1953), Molloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable (trilogy, late 1940s–1950s).

- Why read: Beckett’s late-modernist/minimalist practice—absurd, stripped language—radically rethinks representation, presence and failure; his aesthetic of exhaustion influenced later postmodern irony and negative theology.

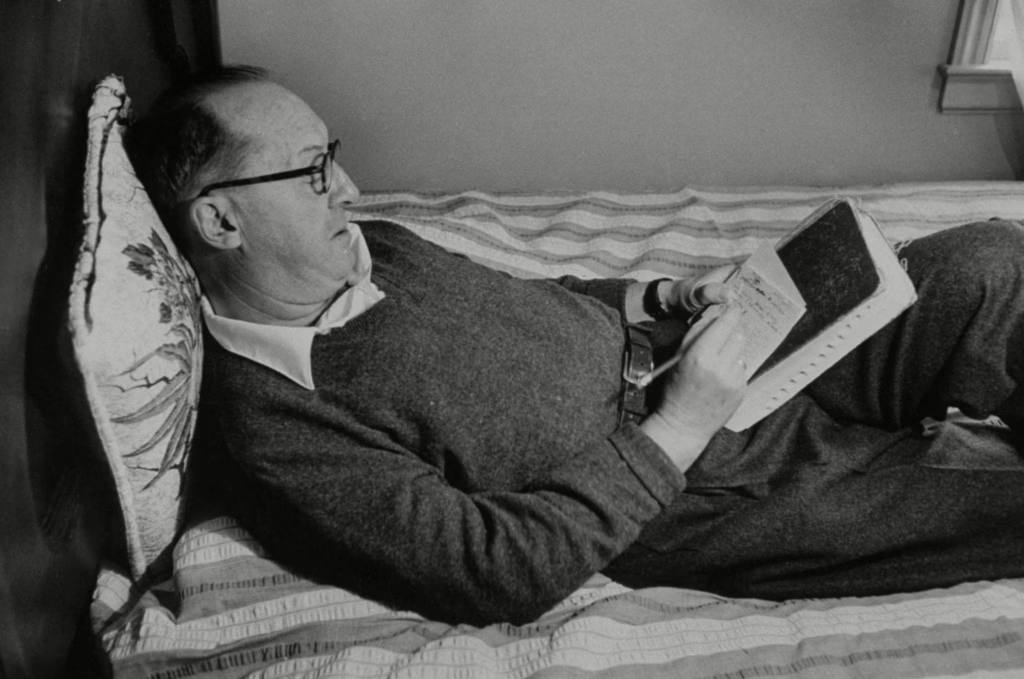

Vladimir Nabokov (Russian/American)

- Key works: Lolita (1955), Pale Fire (1962).

- Why read: Nabokov’s highly artful, self-conscious narration and his play with poetry/fiction (as in Pale Fire) illustrate postmodern gamesmanship and the ethical puzzles of readerly complicity.

B. Anglo-American postmodern novelists (canonical)

John Barth (USA)

- Key works: The Sot-Weed Factor (1960), Lost in the Funhouse (1968).

- Why read: Barth’s metafictional essays and fictions helped define the self-reflexive tendency: his stories often stage “writing about writing” and foreground artifice.

Thomas Pynchon (USA)

- Key works: V. (1963), The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), Gravity’s Rainbow (1973).

- Why read: Pynchon’s encyclopedic novels mix paranoia, historical speculation and dense intertextuality; Gravity’s Rainbow is frequently cited as a high point of postmodern maximalism.

Kurt Vonnegut (USA)

- Key works: Slaughterhouse-Five (1969), Cat’s Cradle (1963).

- Why read: Vonnegut melds satire, science-fiction motifs, and tragicomic humanism — his irony addresses trauma (war) and technological dehumanization while maintaining ethical seriousness.

Don DeLillo (USA)

- Key works: White Noise (1985), Libra (1988), Underworld (1997).

- Why read: DeLillo explores media saturation, cultural paranoia and the commodified American landscape; his prose is spare, allusive and formally attentive to surfaces of late capitalism.

David Foster Wallace (USA)

- Key works: Infinite Jest (1996), Brief Interviews with Hideous Men (1999).

- Why read: Wallace attempted to go beyond postmodern irony with a blend of maximalism and sincerity, exploring addiction, entertainment, and the collapse of communication.

John Fowles (UK)

- Key works: The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1969), The Magus (1965).

- Why read: Fowles uses metafiction and alternate endings to explore free will and narrative control within historical fiction.

C. European postmodernists (not exhaustive)

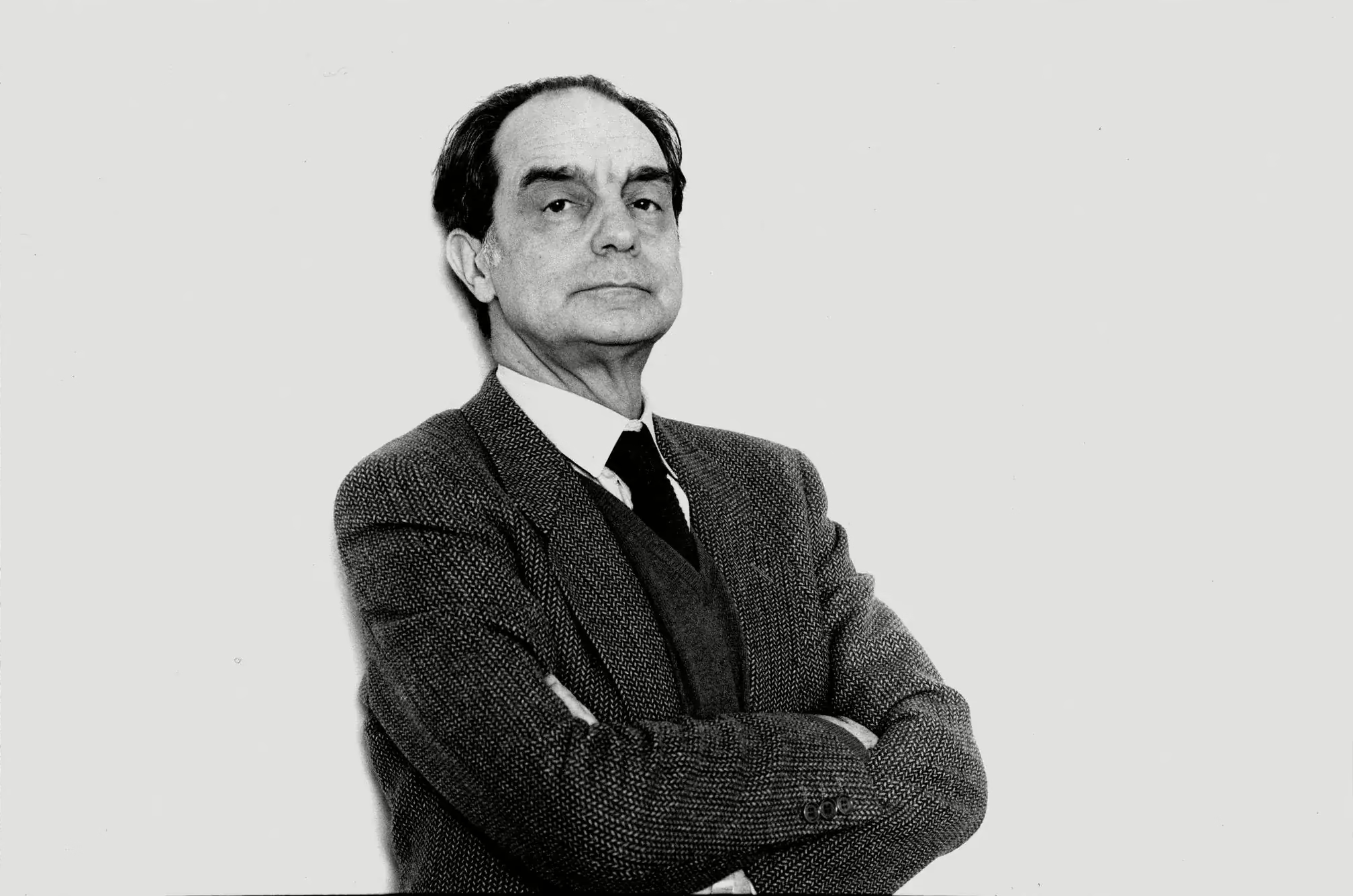

Italo Calvino (Italy)

- Key works: Invisible Cities (1972), If on a winter’s night a traveller (1979).

- Why read: Calvino’s metafictional intelligence and literary fables probe reading, narrative, and the architecture of imagination; his work moves between playful structures and philosophical reflection.

Umberto Eco (Italy)

- Key works: The Name of the Rose (1980), Foucault’s Pendulum (1988).

- Why read: Eco blends semiotics, medieval history and conspiracy in complicated puzzles; his novels exemplify erudite pastiche and theories of textual interpretation.

Milan Kundera (Czech Republic/France)

- Key works: The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979), The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984).

- Why read: Kundera merges philosophy, history, and eroticism in narratives that examine memory, identity, and political amnesia.

D. Postcolonial/postmodern crossovers

Salman Rushdie (India/UK)

- Key works: Midnight’s Children (1981), The Satanic Verses (1988).

- Why read: Rushdie mixes magical realism with historiographic metafiction; Midnight’s Children is a landmark that rewrites national history through hybridity, myth and playful narrative form.

Jeanette Winterson (UK)

- Key works: Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (1985), The Passion (1987).

- Why read: Winterson’s lyric prose, mythic reworkings and queer subjectivities show postmodern play combined with political and sexual self-fashioning.

J. M. Coetzee (South Africa)

- Key works: Foe (1986), Disgrace (1999).

- Why read: Coetzee’s novels interrogate colonial history and narrative voice, often blending allegory with metafictional critique.

Margaret Atwood (Canada)

- Key works: The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), The Blind Assassin (2000).

- Why read: Atwood uses speculative fiction and layered narratives to critique patriarchy, environmental crisis, and historical amnesia.

Toni Morrison (USA)

- Key works: Beloved (1987), Jazz (1992).

- Why read: Morrison’s complex structures and spectral themes contribute to a postmodern exploration of trauma, memory, and Black identity in American history.

Zadie Smith (UK)

- Key works: White Teeth (2000), On Beauty (2005).

- Why read: Smith’s novels explore multicultural Britain with polyphonic voices and hybrid forms that reflect postcolonial/postmodern convergence.

E. Contemporary and late/post-postmodern voices

Mark Z. Danielewski (USA)

- Key works: House of Leaves (2000)

- Why read: A cult postmodern novel using typographic experimentation, narrative layering, and marginal commentary to explore madness, textual instability, and spatial horror.

Ali Smith (UK)

- Key works: How to Be Both (2014), Autumn (2016)

- Why read: Smith’s novels combine political immediacy with formal innovation (e.g., dual narratives, gender fluidity), reasserting aesthetic experimentation in contemporary British fiction.

Roberto Bolaño (Chile/Spain)

- Key works: The Savage Detectives (1998), 2666 (2004)

- Why read: Bolaño merges postmodern fragmentation with moral urgency and literary obsession. His sprawling works are labyrinths of violence, disappearance, and textual pursuit.

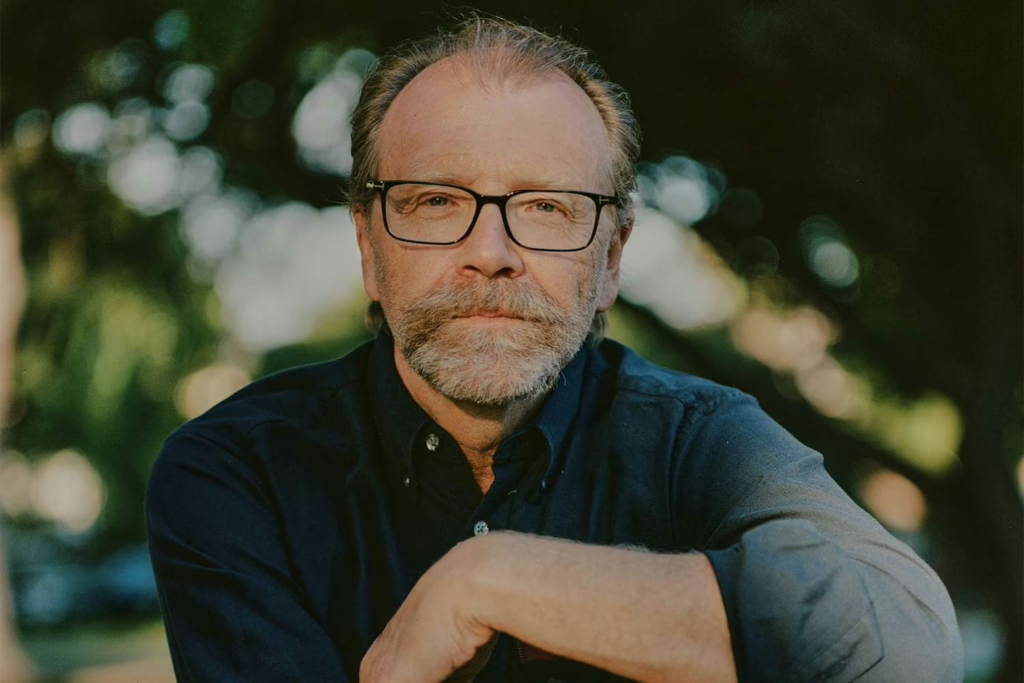

George Saunders (USA)

- Key works: Tenth of December (2013), Lincoln in the Bardo (2017)

- Why read: Saunders blends satire, speculative fiction, and spiritual inquiry in short stories and novels that explore empathy, dislocation, and collective voice.

Rachel Cusk (UK)

- Key works: Outline (2014), Transit (2016), Kudos (2018)

- Why read: Known for her autofictional “Faye” trilogy, Cusk uses minimalist, dialogic narration to challenge subjectivity and narrative authority in contemporary literary form.

Teju Cole (Nigeria/USA)

- Key works: Open City (2011), Blind Spot (2017)

- Why read: Cole’s prose combines essay, fiction, photography, and criticism to form meditative, border-crossing texts that reflect on history, urban life, and perception.

For lists of canonical postmodern novels and further reading see consolidated bibliographies and public lists (comprehensive lists with publication dates are available online). (Wikipedia)

V. Short summaries and reading-entry points for landmark postmodern works

Below are succinct but analytically rich summaries of several widely taught texts. Each is written to support seminar-level close readings.

1. Gravity’s Rainbow — Thomas Pynchon (1973)

Form & structure: This encyclopedic novel, exceeding 750 pages, uses fragmented narrative, shifting perspectives, nonlinear chronology, and a dizzying array of characters. Set at the end of World War II, it revolves around the V-2 rocket and the American lieutenant Tyrone Slothrop, whose bodily reactions are eerily linked to rocket strikes.

Themes & motifs:

- Paranoia as both narrative driver and epistemological condition.

- The interpenetration of science, technology, war, and capitalism.

- The question of free will vs determinism in bureaucratic and physical systems.

- Myth, Kabbalah, and tarot as interpretive tools embedded in a postmodern cosmology.

Reading strategies:

- Trace the structure through the rocket launch trajectory (a parabola) as metaphor.

- Study the layering of popular culture, scientific discourse, and paranoia to examine Pynchon’s critique of modernity.

- Use critical theory (e.g., Deleuze and Guattari, Jameson) to decode how the novel operates as postmodern totality.

2. Slaughterhouse-Five — Kurt Vonnegut (1969)

Form & structure: Combining science fiction, autobiography, and war memoir, this novel’s non-linear narrative depicts Billy Pilgrim’s experiences as a soldier, POW during the Dresden bombing, and abductee on the alien planet Tralfamadore.

Themes & motifs:

- Time as nonlinear and deterministic: “so it goes” becomes a refrain.

- Trauma and the challenge of representing atrocity.

- Satire of military-industrial bureaucracy and American consumerism.

Reading strategies:

- Compare with trauma theory: how does disjointed temporality reflect PTSD?

- Investigate Vonnegut’s self-insertion and metafictional technique.

- Explore the ethical dimension of detachment and humor in war literature.

3. If on a winter’s night a traveller — Italo Calvino (1979)

Form & structure: A quintessential metafiction, it alternates between second-person chapters addressing “you” the reader, and ten first chapters of imaginary novels. The result is a recursive and self-conscious meditation on the act of reading.

Themes & motifs:

- The illusion of narrative unity.

- Readerly desire, interruption, and narrative authority.

- Intertextual pastiche of different literary genres.

Reading strategies:

- Examine Calvino’s parody of genres (spy novel, romance, political thriller).

- Theorize the reader’s role using Barthes’ “Death of the Author” and reader-response theory.

- Study the interplay between desire, knowledge, and incompleteness.

4. Midnight’s Children — Salman Rushdie (1981)

Form & structure: A rich blend of magical realism and postcolonial historiography. Narrated by Saleem Sinai, born at the moment of Indian independence, the novel fuses personal and national history in non-linear, looping narrative.

Themes & motifs:

- Postcolonial identity and hybridity.

- History as subjective, contested, and mythologized.

- Language as both colonial legacy and means of resistance.

Reading strategies:

- Analyze Saleem’s self-conscious narration as historiographic metafiction.

- Explore the novel’s intermingling of the mythic and the real.

- Trace the narrative’s critique of nationalism and political failure.

5. Beloved — Toni Morrison (1987)

Form & structure: Set after the American Civil War, it follows Sethe, a formerly enslaved woman haunted by the ghost of her daughter. The narrative moves fluidly through past and present, memory and trauma.

Themes & motifs:

- Memory as spectral, nonlinear, and embodied.

- The politics of witnessing and silence.

- Slavery’s legacy and the difficulty of historical narration.

Reading strategies:

- Use trauma theory (Caruth, Felman) to examine the ethics of representation.

- Investigate Morrison’s narrative disruptions as formal correlates of trauma.

- Examine the use of supernatural as symbolic reclamation of suppressed history.

6. White Noise — Don DeLillo (1985)

Form & structure: A suburban satire structured in three parts, this novel explores a family’s mundane life disrupted by an airborne toxic event. The narrative is spare and steeped in media soundscapes.

Themes & motifs:

- Death and the fear of dying in a consumerist, media-saturated world.

- Language as a buffer between self and reality.

- Simulation vs. authenticity in the age of infotainment.

Reading strategies:

- Examine how DeLillo critiques consumerism and media through repetition.

- Study the theme of hyperreality via Baudrillard’s theory.

- Analyze how the characters’ speech patterns reflect commodified consciousness.

7. Pale Fire — Vladimir Nabokov (1962)

Form & structure: A poem (999 lines) by fictional poet John Shade, accompanied by a commentary by Charles Kinbote, whose annotations hijack the text into a delusional alternative narrative.

Themes & motifs:

- Authorship and textual authority.

- Paranoia, identity, and narrative control.

- The instability of meaning and textual multiplicity.

Reading strategies:

- Treat Kinbote as both narrator and unreliable reader.

- Explore theories of authorship and reception (Foucault, Barthes).

- Trace metafictional tension between poem and commentary.

8. The Crying of Lot 49 — Thomas Pynchon (1966)

Form & structure: A compact and enigmatic novella that follows Oedipa Maas as she uncovers the mysterious Trystero postal system, which may or may not be a vast historical conspiracy.

Themes & motifs:

- Conspiracy and information overload.

- Communication, entropy, and interpretation.

- Paranoia and the search for meaning in a fragmented world.

Reading strategies:

- Explore post-structuralist concerns with interpretation and multiplicity.

- Analyze the novel as a precursor to Pynchon’s later maximalist style.

- Compare Oedipa’s quest with detective fiction conventions and how they are subverted.

9. Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit — Jeanette Winterson (1985)

Form & structure: A semi-autobiographical Bildungsroman that blends narrative, myth, and fairytale to tell the story of a young lesbian growing up in a Pentecostal community in England.

Themes & motifs:

- Sexual identity and religious dogma.

- Myth as counter-narrative.

- The construction and deconstruction of autobiography.

Reading strategies:

- Examine the hybrid narrative form—alternating realist memoir with fable-like interludes.

- Discuss Winterson’s use of intertextuality and metafiction to critique heteronormativity.

- Explore how feminist and queer theory inform textual analysis.

10. Infinite Jest — David Foster Wallace (1996)

Form & structure: A sprawling, non-linear novel that interweaves the lives of tennis academy students, recovering addicts, and shadowy political operatives. Known for its extensive use of footnotes and nested narratives.

Themes & motifs:

- Addiction, entertainment, and self-destruction.

- Sincerity vs. irony in late capitalism.

- Language, fragmentation, and systems of control.

Reading strategies:

- Analyze Wallace’s self-reflexive commentary on postmodernism’s limits.

- Discuss how the novel critiques both mass entertainment and postmodern detachment.

- Trace the thematic interplay between form and content (e.g., footnotes as a device of fragmentation).

11. The French Lieutenant’s Woman — John Fowles (1969)

Form & structure: A Victorian pastiche that includes metafictional interjections, multiple endings, and an intrusive narrator.

Themes & motifs:

- Free will vs. determinism.

- Gender roles and historiography.

- The nature of authorship and narrative authority.

Reading strategies:

- Examine the narrator’s role as a metafictional figure.

- Compare with actual Victorian novels to highlight parody and anachronism.

- Explore the tension between modern sensibility and historical setting.

VI. Major critical currents and theories that shaped/post-shaped postmodern writing

Postmodern literature both drew on and activated theoretical conversations. The most influential theoretical currents include:

- Post-structuralism and deconstruction (Derrida): Language’s instability and the impossibility of final meaning; this influences metafictional and citation-heavy strategies.

- Lyotard’s “postmodern condition”: Loss of faith in grand narratives — translated in literature as scepticism about totalising historical or political stories.

- Foucault’s archaeology/genealogy: Power/knowledge struggles and discursive formation influence historiographic metafiction and novels that examine institutional narratives.

- Semiotics and Baudrillard: Simulation, hyperreality and the collapse of representation feed novels that stage media-saturated worlds.

- Feminist, postcolonial, queer and minority critiques: These interventions exposed the centrality of race, gender, and empire to canon formation, pushing postmodern literature toward plural authorship and alternative narrative strategies. (Oxford Bibliographies)

VII. Thematic clusters — how postmodern texts approach the world

Below are recurring thematic complexes that students should map across different texts.

1. History as narrative vs history as catastrophe

- Many postmodern novels stage the unreliability of historiography (e.g., Eco, Rushdie, Pynchon). Historiographic metafiction makes readers question the truth-claims of history.

2. Trauma, memory and representation

- Postwar trauma literature and postcolonial narratives interrogate how personal and collective traumas are remembered and narrated (Owen, Morrison, Kureishi, W. G. Sebald).

3. Language, play and ethics

- Formal playfulness (pastiche, parody) can be ethically ambivalent: it can free the text from grand narratives but can also ironically distance the reader from moral responsibility. Some late postmodern writers (e.g., David Foster Wallace) explicitly try to reintroduce ethical concern into ironic practice.

4. Identity, hybridity and diaspora

- Migrant and diasporic authors depict hybrid identities and create new narrative forms that mix languages and cultural logics: Rushdie, Zadie Smith, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

5. Media, simulation and commodification

- Postmodern texts frequently represent media-saturated life; DeLillo’s White Noise and Don Delillo’s later novels exemplify this preoccupation.

VIII. Genres, modes and crossovers

Postmodern writing thrives on cross-genre experiments:

- Historiographic metafiction (e.g., Rushdie, Eco).

- Speculative/dystopian fictions as ideological critique (Atwood, Huxley earlier, DeLillo).

- Detective and noir reworkings (Eco’s semiotic detective, Bolaño’s crime/epic).

- Memoir/auto-fiction — blurring the line between autobiography and invention (e.g., Karl Ove Knausgård recently, though Scandinavian).

- Digital/hypertext fiction — experiments with nonlinear reading; visual and code-based narratives in digital literature.

IX. Debates, criticisms and evolving perspectives

Scholarly and cultural debates about postmodernism fall into familiar camps:

- Is postmodernism politically vacuous? Critics like Fredric Jameson charged postmodernism with cultural logic of late capitalism (depthless pastiche); others defend postmodern techniques as necessary to critique power and ideology.

- Is “postmodern” still useful? Some scholars propose “post-postmodern” categories (e.g., metamodernism, the new sincerity) arguing for renewed ethical and affective commitments in 21st-century art.

- Can humour and irony coexist with moral seriousness? The tension between playful form and political seriousness is often disputed. Writers such as Wallace, Morrison and Atwood are read as demonstrating that ethical depth and formal playfulness can coexist.

For critical overviews see major handbooks and bibliographies; Oxford Bibliographies and the Oxford Handbook of Postmodern Studies provide entry points. (Oxford Bibliographies)

X. Teaching suggestions: modules, close-reading foci and exam questions

Suggested seminar modules

- Metafiction and the ethics of narration: Barth, Calvino, Eco.

- Postmodernism and war: Pynchon, Vonnegut, Sebald.

- Postcolonial rewritings of history: Rushdie, Achebe, Márquez.

- Media, simulation and consumer culture: DeLillo, Don Delillo, post-1980s novels.

- Late postmodern and post-postmodern moves: David Foster Wallace, Zadie Smith, Kazuo Ishiguro.

Close-reading focus prompts

- Analyse the role of intertextuality in Pale Fire: how does the commentary structure rework authorial authority?

- Compare narrative unreliability in The Crying of Lot 49 and If on a winter’s night a traveller. How do both novels make the reader a detective?

- Read Beloved through the concept of historiographic metafiction: in what sense does Morrison’s novel interrogate historiography?

Exam-style questions

- “Discuss how historiographic metafiction disrupts traditional history/fiction boundaries. Illustrate with two novels.”

- “How does postmodern irony function politically? Is it a tool of critique or of detachment?”

- “Trace the influence of mass media on postmodern narrative techniques.”

XI. Annotated bibliography and editions

Introductory handbooks and reference

- Encyclopaedia Brittanica, “Postmodernism” — accessible overview of the movement’s tendencies and debates. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- Oxford Reference / Oxford Handbooks — entries on postmodernism and key concepts (pastiche, metafiction). (Oxford Reference)

- Oxford Bibliographies — curated bibliographies and annotated reading lists for postmodernism and linked theoretical fields. (Oxford Bibliographies)

Key primary texts (recommended scholarly editions)

- Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow (Viking/Penguin modern classics).

- Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five (Dial Press/Penguin).

- Italo Calvino, If on a winter’s night a traveller (Vintage/Everyman).

- Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children (Vintage).

- Jorge Luis Borges, Ficciones (Penguin Modern Classics).

- Toni Morrison, Beloved (Vintage).

- David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest (Little, Brown) — and his essays collection.

- Don DeLillo, White Noise (Penguin Modern Classics).

Scholarly studies (advanced)

- Linda Hutcheon, A Poetics of Postmodernism — seminal account of historiographic metafiction.

- Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism — influential Marxist critique.

- Brian McHale, Postmodernist Fiction — formalist study of postmodern techniques.

- Brian McHale and others in the Cambridge Companion series (Modern and Contemporary).

- Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition — philosophical framing (translated).

XII. Limitations, tendentiousness and further directions

- Canon bias: This chapter foregrounds widely-taught writers but cannot fully represent regional, language-specific or small-press experiments. Many vibrant literatures (African, Asian, Latin American) have their own postmodern inflections that deserve independent, in-depth treatment.

- Ongoing change: The period continues; “postmodern” has been rethought by new theoretical moves (ecocriticism, digital humanities, queer & race studies). Readers should approach the label critically and comparatively.

- Interdisciplinary approach recommended: Postmodern literature benefits from being read alongside theory, film studies, visual arts and media studies because many of its tactics are cross-media.

XIII. Concluding synthesis

The Postmodern Age (1945–present) is a plural and contested epoch in which literature reflexively examines its own tools while interrogating the conditions of history, media and identity. Postmodern techniques — irony, pastiche, metafiction, intertextuality — are not merely stylistic quirks; they are formal responses to social, political and epistemological fractures produced by war, decolonisation, mass media and global capitalism. Contemporary debate now asks: what follows postmodernism? Many contemporary authors recombine postmodern play with renewed ethical aims and new media forms; it is therefore profitable to study postmodern literature not as a closed canon but as an ongoing set of practices from which later writers continue to borrow and revise.