The English Renaissance period (c. 1500–1660) is one of the richest and most transformative stretches in the history of English letters. It is the period in which England absorbs and re-creates the classical heritage of Greece and Rome, internalizes humanist learning, expands the expressive range of English, and produces some of the greatest works in drama, poetry, and prose. The period coincides with profound social, political, religious, and scientific change: the Reformation and religious settlement, the rise of nation-state consciousness, expansion overseas, the invention and spread of printing, and the intellectual ferment of early modern science. Those changes shaped the themes, forms, and concerns of writers and created new audiences — courts, courts of opinion, and a growing reading public.

This chapter provides a higher-study level treatment: (1) a tightly dated timeline of major events and their literary impact; (2) an extended discussion of the conventional subdivisions (Early Tudor, Elizabethan, Jacobean, Caroline/Commonwealth), with features for each; (3) categorical lists of major authors and works; (4) concise critical summaries of central works; (5) thematic, linguistic, and generic analysis; and (6) concluding remarks on legacy and recommended readings.

Precise chronological frame used in this chapter: c. 1500 (proto-Renaissance humanism visible in England) → 1660 (Restoration of Charles II; commonly taken as an end-marker for the Renaissance in England). Note that important compositions and publications may fall a few years outside these limits (e.g., Milton’s Paradise Lost 1667), but Milton’s writing life is embedded in the late Renaissance/Commonwealth crisis and is discussed here with careful dating.

I. Major historical events (1500–1660) and their literary impacts

Below are the pivotal political, religious, technological, and cultural events that shaped literary production. Each event entry is followed by the direct and traceable impacts on literature.

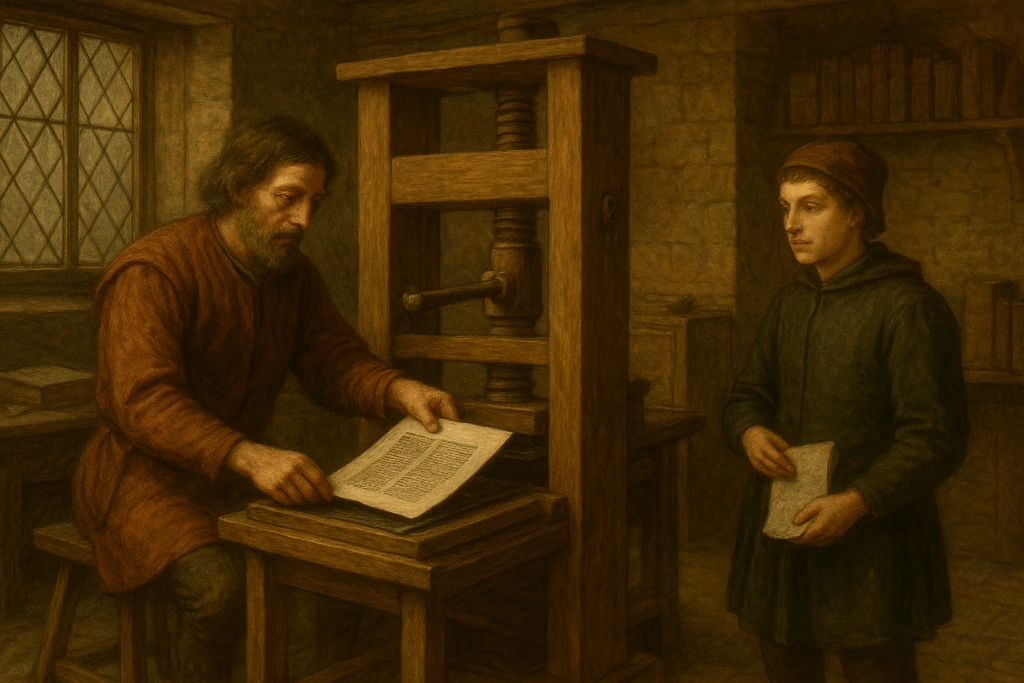

1. The Printing Press and the Spread of Print (late 15th century → 16th century)

- Impact: Faster dissemination of texts; standardization of language; growth of vernacular reading; cheaper books and pamphlets broadened audience beyond elite patrons; made possible the rapid circulation of Reformation tracts, humanist texts, and plays.

2. Tudor Consolidation & Humanist Education (Henry VII–Elizabeth I, late 15th–16th c.)

- Impact: Court patronage supports poets and translators; universities (Oxford, Cambridge) become channels for humanist learning; classical models (Virgil, Ovid, Seneca) inform forms (sonnet, tragic structure, epic imitation); humanist emphasis on rhetorical skill and moral instruction enriches prose and poetry.

3. The Protestant Reformation & Henry VIII’s Break with Rome (c. 1530s)

- Impact: Religious controversy produces polemical prose, translations of Scripture into English, sermons, and devotional writing; the vernacular Bible expands the audience and influences idiom and tone (culminating in the King James Bible, 1611).

4. The Elizabethan Settlement & Cultural Flourishing (1558–1603)

- Impact: Political stability under Elizabeth I produces a court culture that patronizes drama, lyric poetry, and narrative poetry; the theater becomes a public institution; national confidence fosters innovations in drama and lyric.

5. Age of Exploration & Imperial Expansion (late 16th–early 17th c.)

- Impact: Greater knowledge of the world and encounters with other cultures feed travel literature, heroic narratives, and themes of discovery and identity (e.g., Hakluyt’s collections, Raleigh’s writings).

6. The Development of Professional Drama (late 16th–early 17th c.)

- Impact: The growth of permanent playhouses (e.g., The Globe) and acting companies encourages dramatic specialization; professional playwrights (Shakespeare, Marlowe, Jonson) write for mixed audiences, refining dramatic verse and characterization.

7. The Jacobean Court & Intellectual Shifts (1603–1625)

- Impact: James I’s patronage extends literary culture but the mood becomes less celebratory and more ambivalent; Jacobean drama often emphasizes darkness, irony, and moral complexity.

8. Religious and Political Tensions → Civil War (1642–1651)

- Impact: Censorship of the stage under Puritan influence, closure of theaters (1642), rise in polemical and pamphlet literature, and prose interventions in politics and theology (Milton’s polemical writings, Hobbes’ political theory).

9. The Commonwealth & Protectorate (1649–1660)

- Impact: The public sphere becomes intensely politicized; pamphlets, sermons, and political tracts proliferate; some poets (Milton, Marvell) write political and religious polemic and continue a high literary standard in difficult conditions.

10. Restoration (1660) — end marker for this chapter

- Impact: Restoration of the monarchy ushers in new theatrical forms and tastes and marks a transition into the neoclassical sensibilities that dominate the later 17th century. Historically, 1660 is commonly used as the end boundary for discussions of the English Renaissance.

II. Subdivisions of the English Renaissance and their defining features

The English Renaissance is usefully divided into four historical/literary phases; each has distinctive tendencies and representative authors.

A. Early Tudor Age (c. 1500–1558) — “Introduction of Humanism”

Defining features:

- Humanist scholarship arrives from continental Europe.

- Translation and adaptation of classical and continental works into English (e.g., Thomas More’s Utopia in Latin but widely read; Tyndale’s Bible fragments and early English biblical translations).

- The sonnet and other Italianate forms begin to be experimented with (Wyatt, Surrey).

- Courtly poetry and didactic prose are prominent; descriptive and moral writing are valued.

- Language: Transition from late Middle English forms to a more flexible, expanding vocabulary that absorbs Latin/French learning.

Representative authors and forms:

- Sir Thomas More (Utopia — Latin, 1516)

- Sir Thomas Wyatt, Earl of Surrey (sonnets, translations of Petrarch)

- Early translators and clerical writers (Tyndale, Erasmus’ influence through scholars)

B. Elizabethan Age (1558–1603) — “Golden Age of Drama and Lyric”

Defining features:

- Dramatic explosion: mature public theater; playwrights combine classical models with English popular traditions.

- Lyric poetry in the sonnet tradition (e.g., Sidney, Spenser) flourishes.

- National self-confidence and courtly culture underpin literary patronage and subject matter.

- Broadening of genres: epic (Spenser), pastoral, lyric, and civic poetry.

Representative authors and forms:

- Edmund Spenser (The Faerie Queene, 1590–96), Sir Philip Sidney (Astrophel and Stella), Christopher Marlowe (heroic tragedy), William Shakespeare (complete dramatic and poetic corpus).

- Prose: travel writing (Richard Hakluyt), devotional prose, and critical works (Sidney’s Defence of Poesie).

C. Jacobean Age (1603–1625) — “Darkness and Complexity”

Defining features:

- Political and religious tensions increase; literature becomes more introspective, ambiguous, and morally complex.

- Drama explores darker themes: corruption, moral ambiguity, revenge tragedy.

- Metaphysical poetics and the tensions of private conscience come to prominence late in this phase.

- The King James Bible (1611) impacts style and lexical resources.

Representative authors and forms:

- Shakespeare (late romances and tragedies), Ben Jonson (satire and classical forms), John Donne (metaphysical poetry), John Webster (revenge tragedy), Francis Bacon (essays).

D. Caroline & Commonwealth Period (1625–1660) — “Crisis, Polemic, and Sublime”

Defining features:

- Reign of Charles I, Civil War, execution of the king, Cromwell’s Protectorate.

- Theaters closed 1642; dramatic production declines in public venues; political and religious prose (pamphlets, sermons) proliferate.

- Poets and prose writers address political theology, liberty, and censorship; Milton’s prose defense of liberty of press (Areopagitica, 1644) and his lyric/pastoral works (e.g., Lycidas, 1637) prefigure epic ambitions.

- The period’s literature is charged, often polemical, and frequently experimental in voice and structure.

Representative authors and forms:

- John Milton (Lycidas; Areopagitica; epic composition ongoing), Andrew Marvell (political lyric), George Herbert (religious poetry), Robert Herrick (carpe diem and lyric).

III. Major genres and a categorical list of authors & works

Below are the principal genres with their representative authors and their outstanding works. After the lists, the chapter supplies short summaries of the most important works.

1. Drama (public and court drama)

- Christopher Marlowe — Tamburlaine (c. 1587), Doctor Faustus (c. 1592), Edward II.

- William Shakespeare — Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Tempest, Richard II, Henry IV Parts, etc.

- Ben Jonson — Volpone, The Alchemist, Sejanus.

- John Webster — The Duchess of Malfi, The White Devil.

- Thomas Kyd — The Spanish Tragedy.

- Thomas Middleton — Women Beware Women, The Changeling.

2. Lyric and Narrative Poetry

- Edmund Spenser — The Faerie Queene (books published 1590, 1596).

- Sir Philip Sidney — Astrophel and Stella (sonnet sequence), The Defence of Poesie.

- John Donne — Songs and Sonnets, Holy Sonnets.

- George Herbert — The Temple.

- Ben Jonson — lyric poetry and masques.

- John Milton — Lycidas (1637; pastoral elegy), Comus (1634; masque).

3. Prose: Humanist, Religious, Scientific, and Political

- Thomas More — Utopia (1516; Latin).

- Francis Bacon — Essays, The Advancement of Learning, Novum Organum (scientific method).

- John Foxe — Acts and Monuments (Foxe’s Book of Martyrs).

- Richard Hakluyt — Principal Navigations (compilations of travel/expedition narratives).

- King James Bible (committee, 1611) — major influence on English prose style.

- John Milton — Areopagitica (1644).

- Thomas Hobbes — Leviathan (1651 — political theory written during the period’s turbulence).

4. Sermons, Devotional Writing, and Religious Poetry

- George Herbert — The Temple (religious lyric).

- John Donne — sermons and devotional poems.

- John Bunyan (slightly later; Pilgrim’s Progress is 1678 but affected by this tradition).

5. Masques and Courtly Entertainment

- Ben Jonson (with Inigo Jones) — court masques (The Masque of Blackness, etc.).

- John Donne, Milton, and others contributed to courtly entertainments and occasional poetry.

IV. Concise summaries and close descriptions of major works (selective; essential for higher study)

Below are compact summaries that foreground each work’s formal features, themes, historical significance, and suggested interpretive angles.

Thomas More — Utopia (1516)

A Latin civic satire that imagines an island commonwealth (Utopia) organized on rational lines: communal property, religious toleration, and an emphasis on civic virtue. More’s work uses dialogues and paradox to critique English social inequalities and the politics of enclosure. It’s vital for understanding Renaissance humanist critique of society and the utopian template for later political thought.

Study angles: humanist rhetorical strategies, irony and authorial stance (More as narrator vs. More the author), the ambivalence of reform proposals.

Sir Thomas Wyatt & Earl of Surrey — Sonnets and Translations

Wyatt and Surrey introduce the Petrarchan sonnet to English practice and adapt Italian meters to English iambic forms. Surrey’s innovations include the English (Shakespearean) sonnet form and blank verse experiments.

Study angles: translation as creative adaptation, emergence of personal lyric voice in English, technical innovations (blank verse).

Edmund Spenser — The Faerie Queene (Books I–III, 1590; additional books 1596)

An allegorical epic celebrating virtue, produced in Spenserian stanza (ababbcbcc). It combines chivalric romance, moral allegory, and national mythmaking. Spenser writes to praise Elizabeth I while exploring moral and theological virtues.

Study angles: allegory vs. literal reading; medieval romance vs. Renaissance humanist epic; Spenserian stanza’s musicality; nationalism and Protestant identity.

Sir Philip Sidney — Astrophel and Stella; The Defence of Poesie (1579)

Astrophel and Stella is a sonnet sequence exploring desire and poetic selfhood. The Defence of Poesie argues for poetry’s ethical and imaginative power against puritanical critics.

Study angles: poet as moral oracle; Renaissance poetics of imagination; Petrarchan conventions revised for English concerns.

Christopher Marlowe — Doctor Faustus; Tamburlaine

Marlowe’s plays dramatize overreaching ambition, the Renaissance desire for knowledge and power, and tragic consequences. Marlowe’s blank verse is muscular and rhetorical; his protagonists are energized and transgressive.

Study angles: Renaissance humanism’s dark side; the Faustian bargain as moral and metaphysical problem; spectacle and rhetorical virtuosity.

William Shakespeare — Selected major works

Because Shakespeare’s oeuvre is central and vast, the following short notes highlight representative plays and their study focus.

Tragedies

- Hamlet — soliloquy and inwardness; action vs. thought; revenge ethics and theatricality.

- King Lear — family and political order; suffering and redemption; nature of authority.

- Othello — race, jealousy, rhetoric, and tragic manipulation.

- Macbeth — ambition, supernatural influence, and limits of agency.

Comedies

- As You Like It — pastoral, identity, and gender play.

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream — romance, illusion, and poetic imagination.

- Twelfth Night — desire, disguise, and social comedy.

Histories

- Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V — questions of kingship, legitimacy, and national identity.

Late Romances

- The Tempest — art and authority, colonial undertones, reconciliation and theatrical closure.

Study angles: genre fluidity; psychological depth; language and rhetorical power; interplay between public/political and private/psychological spheres.

Ben Jonson — Volpone; The Alchemist; Masques

Jonson’s comedies satirize greed, gullibility, and social mores with sharp classical decorum and moralizing comedy. His masques, often in collaboration with Inigo Jones, express courtly aesthetics.

Study angles: Jonsonian classicism vs. Shakespearean naturalism; satirical targets and moral instruction; urban social comedy.

John Donne — Selected poems and sermons

Donne’s conceits and metaphysical style fuse passionate lyricism with intellectual rigor. Poems like A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning, The Sun Rising, and his Holy Sonnets combine erotic, devotional, and philosophical concerns.

Study angles: metaphysical conceits; paradox and wit; the collision of sensual and spiritual rhetoric.

John Milton — Lycidas (1637); Areopagitica (1644); Epic project (Paradise Lost composed 1658–1663; first edition 1667)

Lycidas is a pastoral elegy mourning a friend and reflecting on poetic vocation. Areopagitica is Milton’s influential polemic for freedom of the press. The epic project (completed after 1660) is the culmination of Miltonic ambition: a Christian epic that reframes classical models and explores providence, free will, and rebellion.

Study angles: pastoral elegy as Christian lyric; Miltonic rhetoric and republican politics; epic form and theological argument.

Francis Bacon — The Advancement of Learning; Novum Organum

Bacon’s essays and methodological treatises espouse inductive inquiry and a new empirical method — foundational for the scientific revolution and shaping the period’s epistemology.

Study angles: Baconian method and its influence on rhetorical and literary values; science and literature as competing or allied discourses.

V. Themes, stylistic tendencies, and formal innovations

1. Humanism and the Individual

- Focus on the dignity and capacities of the individual; classical knowledge used to teach virtue and civic responsibility.

- Rise of interiority and self-reflection (sonnet, soliloquy) — the poet as thinker and moral agent.

2. Experimentation with Classical Forms

- Adaptation of epic, pastoral, comedy, and tragedy to English needs. Spenser’s epic, Sidney’s pastoral, and the Senecan influence on revenge tragedy show classical models reinterpreted.

3. Language and Style

- Expansion of vocabulary through Latin and French borrowings.

- Experimentation with rhetorical structures: extended ethos, amplified periods, and the development of blank verse (attributed largely to Surrey and perfected by Marlowe and Shakespeare).

4. Public vs. Private Literature

- Court poetry and masques (public spectacle) exist alongside private lyric and devotional writing; drama mediates between these spheres through public performance of private passions.

5. Religion and the Sacred

- Tension between the Protestant emphasis on scripture and humanist literary aesthetics; religious controversy produces chapbooks, sermons, and devotional lyric.

6. Politics, Nationhood, and Identity

- Plays and poems interrogate monarchy, governance, and national destiny (e.g., Shakespeare’s histories; political tracts).

VI. Critical approaches and interpretive frameworks

For higher study, the following critical lenses yield productive readings of Renaissance texts:

- New Historicism / Cultural Materialism: reading texts against social and political contexts — court patronage, censorship, and emergent capitalism.

- Formal and Rhetorical Analysis: close attention to prosody, stanza form (Spenserian stanza), blank verse, and rhetorical figures (conceit in metaphysical poetry).

- Gender and Performance Studies: theatre as a site of gender negotiation (male actors as females); Petrarchan conventions and female voices in lyric and drama.

- Religious and Theological Criticism: how doctrinal change conditions poetry and prose (e.g., Puritanism vs. Anglican ceremonial; Miltonic theology).

- Postcolonial/Global Perspectives: exploration of early modern encounters, voyages, and colonial discourses in travel writing and poetic accounts.

VII. Teaching and research suggestions for higher study

Primary-text clusters for seminars:

- The Faerie Queene (selected books) + Sidney’s Defence (poetics).

- Shakespeare: one tragedy, one comedy, and a history for comparative study (e.g., Hamlet, As You Like It, Henry V).

- Donne + Herbert + George Herbert: the metaphysical and devotional lyric.

- Marlowe + Jonson + Shakespeare: professional playwrights and differing dramatic ideals.

- Milton’s prose (Areopagitica) + Lycidas + sketch of Paradise Lost as genus study.

Research projects & topics:

- The role of print culture in the dissemination of religious controversies.

- Translation practices and the building of an English literary vocabulary.

- The gendered stage: female roles, cross-dressing, and the social implications of theatre.

- Early modern scientific discourse and literary representation (Baconian influence).

VIII. Brief historiography and critical legacy

The English Renaissance has been read through many interpretive lenses. Early scholarship emphasized progress and humanist triumph; later 20th-century critics (New Historicists, feminist scholars, postcolonial critics) stressed power, marginal voices, and the social contexts of production. The Renaissance’s canonical works continue to fuel debates about authorship, textual editing, race, empire, and the boundaries between secular and sacred writing.

Its legacy is immense: Shakespeare’s dramatization of human psychology; the King James Bible’s influence on English idiom; Milton’s epic ambition; Spenser’s nation-building; Donne’s hybrid metaphysical voice — all continue to inform modern poetry, political thought, and narrative form.

IX. Recommended primary editions and secondary readings

Primary texts (accessible scholarly editions):

- William Shakespeare, The Complete Works (Oxford Shakespeare or Arden editions)

- Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene (Longman or Penguin critical editions)

- John Donne, Poems (Oxford / Penguin)

- Ben Jonson, Complete Plays (Oxford)

- Christopher Marlowe, The Complete Plays (Penguin)

- Francis Bacon, Essays and Selected Writings

- John Milton, Selected Poems and Prose (for Lycidas, Areopagitica)

- King James Bible (1611) — select passages to study its linguistic influence

Representative secondary studies and handbooks:

- Greenblatt, Stephen, Renaissance Self-Fashioning (classic New Historicist study)

- A. C. Hamilton, A Companion to the English Renaissance (edited volumes)

- J. B. Leishman / G. Blakemore Evans (eds.), A Companion to Shakespeare Studies

- Lisa Jardine, Worldly Goods (on culture and trade in early modern England)

- Jonathan Bate, The Genius of Shakespeare (accessible critical engagement)

- Barbara Lewalski, The Life of John Milton (for Miltonic studies)

X. Conclusion

The English Renaissance (1500–1660) is a period of extraordinary creativity and transformation. Its writers wrestled with the cultural inheritance of classical antiquity while inventing new forms and idioms in English. They adapted lyric and epic structures, founded national dramatics, developed devotional and polemical prose, and shaped a public literary culture sustained by print. That culture was neither uniform nor unidirectional: it encompassed courtly patronage and popular theatre, humanist optimism and civil-war disillusionment, devotional intensity and satiric worldliness. A sustained study of the period rewards scholars with insight into the ways literature negotiates power, belief, identity, and imaginative possibility — and it prepares students to read later developments (neoclassicism and Romanticism) as responses to, and breaks with, Renaissance achievements.