The Victorian Age — named for the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901) — is one of the most complex, productive, and contradictory periods in English literary history. It is an era of extraordinary social, economic, scientific, and imperial change: industrialization and urban growth accelerate, the British Empire extends to unprecedented global reach, political enfranchisement slowly widens, science challenges received certainties, and mass print culture creates new reading publics. Victorian literature both records and probes these changes: it explores social reform and social pathology; it negotiates faith and doubt after Darwin; it celebrates moral duty yet interrogates hidden hypocrisies; and it creates some of the century’s most enduring fiction, poetry, and criticism.

This chapter provides an advanced, research-ready account of Victorian literature: a carefully dated map of major historical events and their literary effects; a clear subdivision of the era with distinguishing features; categorical lists of major authors and works; analytical summaries of central texts; thematic and formal analysis; context on publishing, readership, and institutions; critical approaches; and a recommended bibliography for deeper study.

I. Major historical events (1837–1901) and their literary impacts

Below are the pivotal political, social, scientific, and cultural events of the Victorian era followed by their direct literary consequences.

1. Industrialization and urbanization (continuing from late 18th c. into 19th c.)

Literary impacts:

- The rise of new social classes (industrial bourgeoisie and urban working classes) becomes the subject of the novel and social investigation.

- Urban squalor and factory labor appear in fictional social critiques (e.g., Dickens’s Hard Times), realist reportage, and social protest literature.

- The figure of the “social novel” (sometimes called the problem novel) emerges to address economic injustice, child labor, slum poverty, and factory conditions.

2. Railways, telegraph, and new communications

Literary impacts:

- Transformed spatial imaginings in literature—speed, mobility, and the compression of time and space. Travel narratives, industrial scenes, and metaphors of networks become widespread. Serialization of novels becomes practical and profitable.

3. The Great Exhibition (1851) and Victorian confidence in progress

Literary impacts:

- Provided images of progress and industrial achievement that writers responded to ambivalently—celebration of human ingenuity alongside worry about dehumanization and materialism.

4. Reform and Extension of the Franchise

- Second Reform Act (1867) and Representation of the People Act (1884) expanded male suffrage in stages (the political process continued beyond 1901).

Literary impacts: - Greater political consciousness in the literature; novels and periodicals engage more explicitly with public opinion and parliamentary politics. Novelists often represent political debate, municipal contention, and class consciousness (e.g., Trollope’s Barchester novels and the later Way We Live Now).

5. Social Movements and Labor Unrest

- Chartism (earlier, but influence persisted), trade unionism, the cooperative movement, and the rise of various social reform campaigns.

Literary impacts: - Writers address class antagonism, reformist and conservative responses, and the dilemmas of political representation in social realist fiction and pamphlets.

6. Irish Famine (1845–1849)

Literary impacts:

- Exposed British governmental failure and provoked debates about empire and responsibility. Irish themes and Anglo-Irish identities enter poetry and prose; the catastrophe influenced realist and social literature.

7. Crimean War (1853–1856) and Imperial Conflicts

Literary impacts:

- War reportage and poetry (Tennyson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade, 1854) shaped public sentiment; literature increasingly examines imperial costs and moral complexity.

8. Indian Rebellion (1857) and imperial consolidation

Literary impacts:

- Prompted reassessment of imperial governance, inspired travel literature and ethnographic writing, and produced contested narratives about “civilization,” race, and governance. Literature of empire (adventure, missionary accounts, imperial romance) expands.

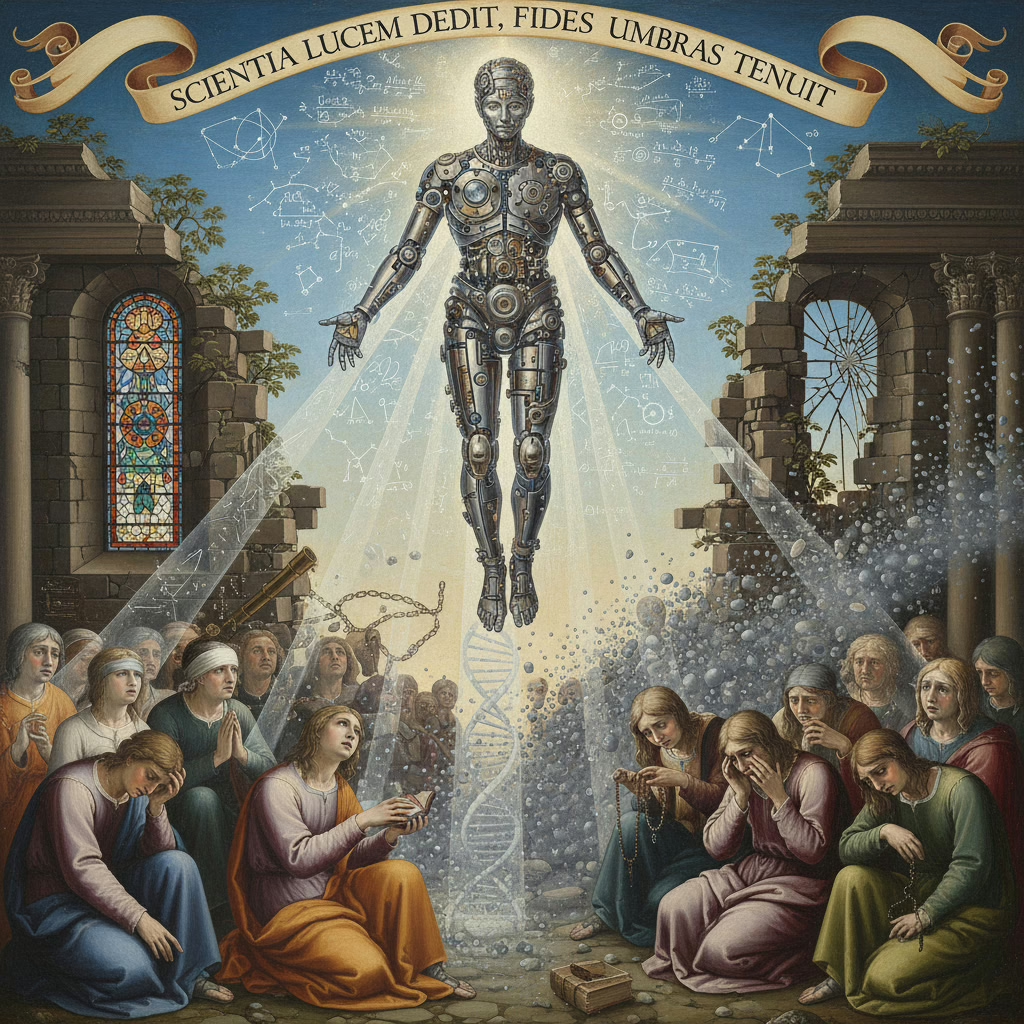

9. The Darwinian Revolution — On the Origin of Species (1859)

Literary impacts:

- Provoked intellectual crisis and creative responses: late-Victorian literature grapples with faith vs. science, the place of humanity in nature, evolutionary metaphors in poetry and fiction, and anxieties about social Darwinism. Writers such as Tennyson, Browning, Hardy, and later novelists reflect Darwinian implications.

10. Intellectual and philosophical ferment: Utilitarianism, Positivism, and Libertarian thought

- John Stuart Mill (On Liberty, 1859) and others shaped debates on individual freedom, utilitarian ethics, and social reform.

Literary impacts: - Novelists interrogate utilitarian ethics versus aesthetic or moral ideals (e.g., Hardy’s tragic realism vs. Mill’s liberal individualism). Literary criticism and essays engage philosophical issues explicitly (e.g., Arnold).

11. Educational reform and literacy growth

- Elementary education acts (1870 and later reforms) and compulsory schooling broaden literate audiences, especially for serialized fiction and periodicals.

Literary impacts: - Expansion of markets for family novels, children’s literature (Lewis Carroll), and serialized fiction attract broad middle-class audiences; reading becomes a social habit.

12. Aestheticism, Decadence, and Fin-de-siècle anxieties (late 19th century)

Literary impacts:

- Reaction against Victorian moral earnestness; the aesthetic movement foregrounds beauty and “art for art’s sake” (Oscar Wilde, Walter Pater, Swinburne). Decadence and Symbolist influences cause stylistic experimentation and moral controversy.

II. Subdivisions of the Victorian Age — periodization and characteristic features

Scholars often subdivide the Victorian Age for analytical clarity. A conventional tripartite division distinguishes:

A. Early Victorian (c. 1837–1850/60) — reform, social conscience, and the social novel

Features:

- Writers confront industrialization’s social effects, the problems of poverty, child labor, and municipal life.

- Novel as the preeminent form for social portraiture (Dickens, Gaskell).

- Moral earnestness and evangelical strains persist; religious debates are still prominent.

Representative authors: Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell, Thomas Carlyle (social polemics), Alfred Lord Tennyson (emergent national poet).

B. Mid-Victorian (c. 1850/60–1870/80) — consolidation, empire, science, and moral reflection

Features:

- After 1850, British material and imperial confidence grows; in literature, formal polish and reflective lyric emerge (Tennyson, Browning).

- Darwinian and utilitarian challenges reshape intellectual discourse.

- Periodical culture matures (Cornhill Magazine, Blackwood’s).

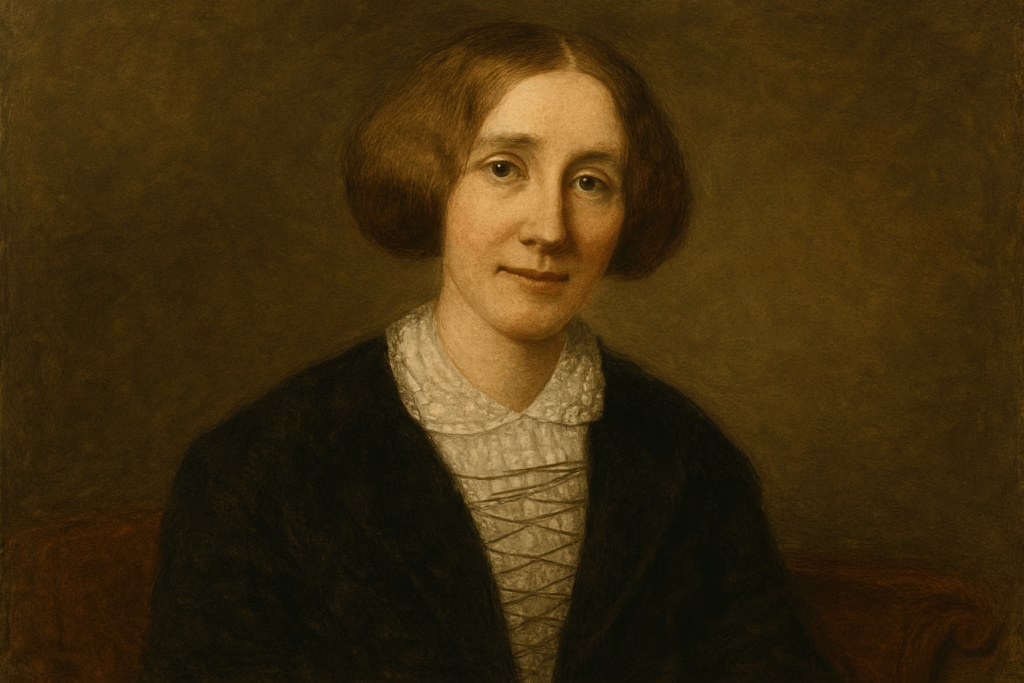

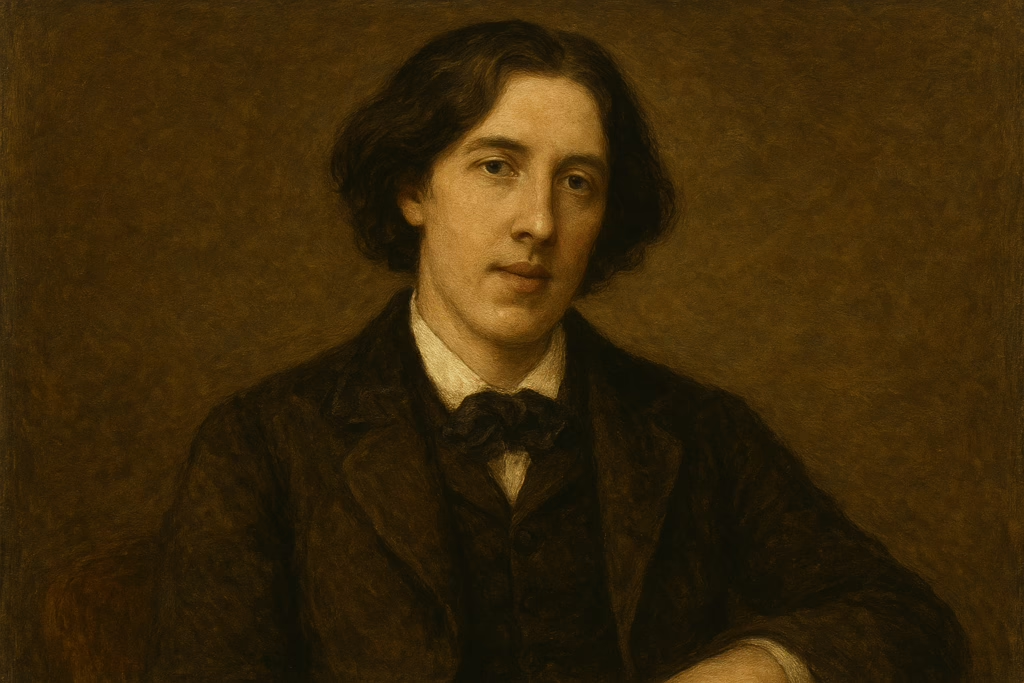

Representative authors: Matthew Arnold (criticism), Robert Browning (dramatic monologue), Elizabeth Barrett Browning, John Ruskin (art criticism), George Eliot (mature realist fiction), Charlotte Brontë’s late work influencing the period.

C. Late Victorian / Fin-de-siècle (c. 1870/80–1901) — realism, aestheticism, imperial critique, modern anxieties

Features:

- The novel diversifies into sensation fiction, realist fiction, imperial adventure, and late realist social critique (Henry James, Thomas Hardy).

- Aesthetic movement and decadence flourish alongside realism.

- Intensified debates about gender, sexuality, science, and empire.

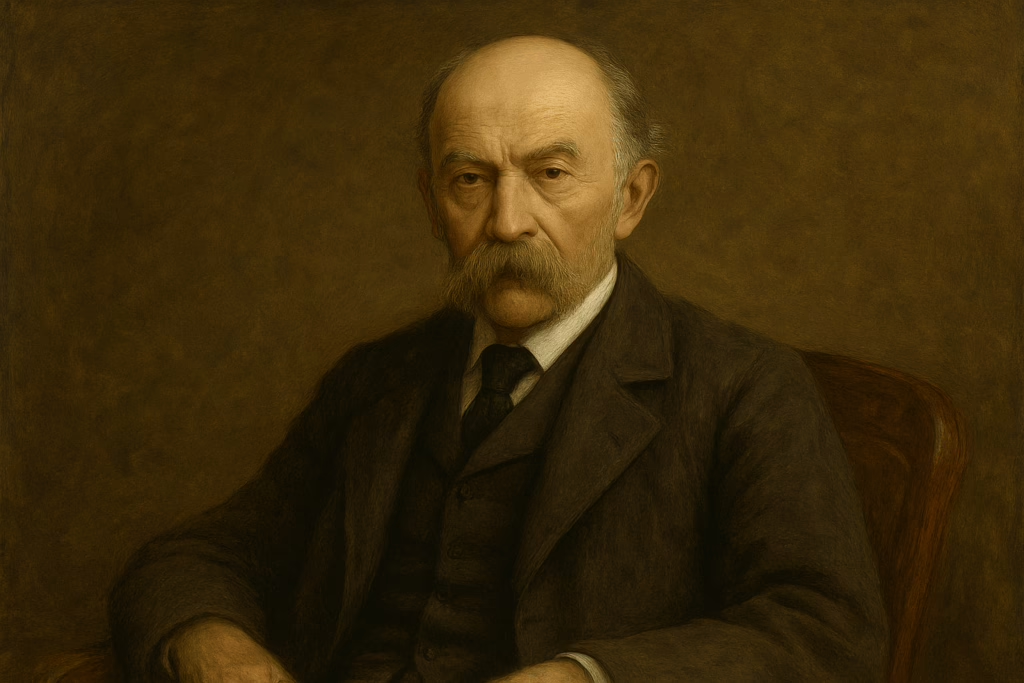

Representative authors: Thomas Hardy, Oscar Wilde, George Meredith, Arthur Conan Doyle (popular fiction), Rudyard Kipling (imperial fiction), Henry James (psychological realism, international themes).

These subdivisions overlap and are porous; authors often cross phases and genres.

III. Literary characteristics, forms, and institutions

1. The Novel as the Dominant Form

Victorian literature is often synonymous with the novel. Forms include:

- Social / industrial novel (Dickens, Gaskell, Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South),

- Realist novel (George Eliot’s psychological realism),

- Sensation novel (Wilkie Collins, e.g., The Woman in White),

- Historical novel (Walter Scott’s influence continues; later G. A. Henty and others),

- Naturalist and tragic novel (Hardy),

- Imperial adventure (H. Rider Haggard and later Kipling),

- Psychological and international novel (Henry James).

Serial publication in periodicals and monthly parts dominates production and reception practices.

2. Poetry: diversity of forms and public poetic voices

Victorian poetry ranges from the public and ceremonial (Tennyson’s national elegies) and dramatic monologues (Browning) to meditative and philosophical lyrics (Arnold), Gothic revival voices (Rossetti), and the Decadent/Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics (Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Christina Rossetti). Poets often engaged with scientific debates and religious doubt.

3. Drama and the Stage

Drama in early Victorian years suffered from censorship and a bourgeois theater; later in the century the stage revitalizes with social problem plays and theatrical innovation. Notable dramatic influence arises from continental developments (Ibsen influence late 19th c.) and domestic comedies (Oscar Wilde’s plays).

4. Periodicals, Reviews, and Print Culture

The Victorian press is central: Household Words (Dickens), All the Year Round, Cornhill Magazine (Thackeray editor), Blackwood’s Magazine, Punch, The Athenaeum and national newspapers shape tastes and provide venues for serialized fiction and essays.

5. Literary Criticism and Cultural Thought

Victorian literary criticism is robust: John Ruskin (art criticism), Matthew Arnold (culture and anomie — Culture and Anarchy), Walter Pater (aesthetic theory), John Stuart Mill (liberal thought) — critics address art’s social function, the relation of beauty and morality, and the role of culture in national life.

IV. Major authors and works — categorical listing (with canonical selections)

Below are the major figures grouped by primary genre or category. This list is selective but covers the central exemplars every higher-studies student should know.

A. Novelists (major)

- Charles Dickens — Oliver Twist (1837–39), Nicholas Nickleby (1838–39), The Old Curiosity Shop (1840–41), A Christmas Carol (1843), David Copperfield (1849–50), Bleak House (1852–53), Hard Times (1854), Little Dorrit (1855–57), Great Expectations (1860–61), Our Mutual Friend (1864–65).

- William Makepeace Thackeray — Vanity Fair (1847–48), The History of Henry Esmond.

- George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) — Adam Bede (1859), The Mill on the Floss (1860), Silas Marner (1861), Middlemarch (1871–72), Daniel Deronda (1876).

- Charlotte Brontë — Jane Eyre (1847).

- Emily Brontë — Wuthering Heights (1847).

- Elizabeth Gaskell — Mary Barton (1848), North and South (1854–55).

- Thomas Hardy — Far from the Madding Crowd (1874), The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), Jude the Obscure (1895).

- Wilkie Collins — The Woman in White (1859), The Moonstone (1868).

- Anthony Trollope — The Warden (1855), Barchester Towers (1857), The Last Chronicle of Barset; The Way We Live Now (1875).

- Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) — Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865).

- Rudyard Kipling — The Jungle Book (1894), Kim (1901) — often placed late-Victorian/Edwardian.

B. Poets (major)

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson — In Memoriam A.H.H. (1850), The Lady of Shalott, Ulysses, The Charge of the Light Brigade (1854).

- Robert Browning — Men and Women (1855; contains “My Last Duchess”), The Ring and the Book (1868–69).

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning — Sonnets from the Portuguese (1850), Aurora Leigh (1856).

- Matthew Arnold — Dover Beach (1867), essays on culture and education.

- Gerard Manley Hopkins (late Victorian, but unpublished in his lifetime; posthumously influential) — innovative prosody (sprung rhythm), religious lyric.

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Christina Rossetti (Pre-Raphaelite circle) — lyric and devotional poetry.

- William Morris — poet, designer, and medievalist; literary romances and utopian writings (e.g., News from Nowhere, 1890).

- Swedenborg/others — less central but engaged with spiritual and mystical themes.

C. Essayists, Critics & Cultural Theorists

- John Ruskin — Modern Painters (1843–60), The Stones of Venice (1851–53); art criticism and social theory.

- Matthew Arnold — Culture and Anarchy (1869), essays and cultural criticism.

- Walter Pater — Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) and aesthetic philosophy.

- John Stuart Mill — On Liberty (1859) — philosophical influence on literary debates.

- Thomas Carlyle — Sartor Resartus (1833–34), essays and social critique.

D. Drama and the Stage

- Oscar Wilde — The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) — comedic satire; Salome (1891).

- George Bernard Shaw (late Victorian/Edwardian transitional) — plays combining social critique and didactic drama (slightly after Victoria’s death but formative during late Victorian decades).

- Stage adaptations (e.g., dramatizations of Dickens and others) were also influential.

E. Travel, Empire, and Adventure

- Rudyard Kipling — poems and imperial narratives; Kim (1901) explores imperial politics and identity.

- H. Rider Haggard — adventure romances (King Solomon’s Mines, 1885; She, 1887).

- Missionary narratives, colonial reports, and travel writing shape imperial consciousness.

V. Extended summaries and analyses of major works

Below are close, interpretively focused summaries of a selection of canonical Victorian works — organized so each summary indicates historical and thematic significance, formal characteristics, and critical angles suitable for higher study.

1. Charles Dickens — Bleak House (serial 1852–1853; book 1853)

Synopsis & Form: Bleak House interleaves two narrative modes — an omniscient third-person narrator and Esther Summerson’s first-person account. It combines social satire, legal critique, Gothic gloom, and sentimental pathos. The central social critique targets the Court of Chancery and the interminable legal case Jarndyce v Jarndyce.

Themes & Significance:

- Bleak House attacks institutional opacity and moral complacency: legal bureaucracy is shown as corrosive to human happiness.

- Social injustice, urban pollution (the fog of London), and charity vs. hypocrisy are central motifs.

- Dickens experiments with narrative technique — multiple narrators, shifting perspectives — producing emotional complexity.

Critical angles: - The novel’s mixed aesthetic of realism and gothic melodrama; gender and domesticity in Esther’s narrative; formal interplay of ironic omniscience and subjective confinement.

2. George Eliot — Middlemarch (serial 1871–72; book 1872)

Synopsis & Form: Set in a provincial town, Middlemarch is a panoramic realist novel with multiple intersecting plots — Dorothea Brooke’s moral ambitions, Tertius Lydgate’s medical reform efforts, Casaubon’s scholarly vanity, and broader social politics. Eliot employs a philosophically reflective narrator with deep psychological insight and moral sympathy.

Themes & Significance:

- Explores the ethics of reform, marriage, knowledge, and the roles of women in social change.

- Presents a sophisticated social realism that links individual character to social structures.

- Noted for psychological depth and moral seriousness; uses free indirect style to render internal thought.

Critical angles: - Eliot’s narrative voice and authorial omniscience; the novel’s ethics of sympathy; representations of provincial modernity; feminism debates — Dorothea’s constrained agency vs. moral aspiration.

3. Thomas Hardy — Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891)

Synopsis & Form: Tess Durbeyfield, a peasant woman of tragic destiny, is repeatedly victimized by social forces, sexual double standards, and a rigid moral order. Hardy’s narrative is naturalistic and fatalistic: chance, heredity, and social constraints conspire to Tess’s downfall.

Themes & Significance:

- Hardy interrogates Victorian sexual morality, class prejudice, and the metaphysical problem of suffering.

- Uses rural realism while exposing the modernizing pressures on agrarian communities.

- Hardy’s blending of archaic fatalism with modern psychology prefigures modernism in tone and bleakness.

Critical angles: - Naturalistic determinism; gendered injustice; narrative voice as both sympathetic and diagnostic; depiction of nature as indifferent or complicit.

4. Alfred, Lord Tennyson — In Memoriam A.H.H. (1850)

Synopsis & Form: Written as an extended elegy mourning Tennyson’s friend Arthur Henry Hallam, the poem is composed in a sequence of short lyric stanzas (iambic tetrameter with an ABBA rhyme scheme). Its meditations move through grief to a tentative religious consolation.

Themes & Significance:

- Addresses grief, faith versus doubt (especially in the wake of scientific advance), and the problem of providence.

- By integrating personal mourning with philosophical reflection, Tennyson creates a national public lyric, widely read and influential.

Critical angles: - Tennyson’s negotiation between faith and modernity; the poem’s formal restraint and musicality; the work as a cultural touchstone for Victorian bereavement and moral education.

5. Charlotte Brontë — Jane Eyre (1847)

Synopsis & Form: A first-person bildungsroman tracing Jane Eyre’s moral and psychological development from orphanhood to self-realization. Her passionate but principled love for Rochester is complicated by social inequality and gothic secrets.

Themes & Significance:

- Gendered autonomy, moral integrity, religious critique (Jane’s spiritual independence), and social mobility are central.

- Combines Romantic intensity with realist detail and proto-feminist assertions of female subjectivity.

Critical angles: - Questions of domestic ideology, Gothic tropes (the madwoman in the attic), and the interplay of class and gender.

6. Emily Brontë — Wuthering Heights (1847)

Synopsis & Form: A complex frame narrative (Lockwood and Nelly Dean) recounts the stormy relationships between Heathcliff and Catherine Earnshaw across two generations. The novel is passionate, violent, and often indeterminate in moral adjudication.

Themes & Significance:

- Explores destructive passion, class resentment, and the interplay of nature and culture.

- Its ambiguous narrative perspective complicates moral evaluation and realism, making it a radical experiment in subjectivity.

Critical angles: - Narrative unreliability, gothic extremes, and the novel’s challenge to Victorian moral ideals.

7. Elizabeth Gaskell — North and South (1854–55)

Synopsis & Form: A social novel contrasting the industrial Northern town of Milton with the genteel South. Margaret Hale’s moral and romantic development unfolds amid conflict between mill owners and workers.

Themes & Significance:

- Industrial conflict, gender roles, and cross-class empathy; presents a balanced exploration of liberal reform vs. radicalism.

- Notable for its fair-minded portrayal of both workers’ grievances and paternalistic mill-owners.

Critical angles: - Victorian civic imagination; women’s roles in moral mediation; Gaskell’s documentary realism about factory life.

8. Charles Dickens — Hard Times (1854)

Synopsis & Form: A short, pointed novel satirizing utilitarianism and industrial capitalism. The fictional town Coketown is a factory-dominated urban environment; characters include the rationalist Mr. Gradgrind, the worker Stephen Blackpool, and the novelist Sleary’s circus as comic counterpoint.

Themes & Significance:

- Critiques educational and economic systems that prioritize facts and utility over human feeling.

- Dickens’s allegorical town and pedagogic satire make the novel a concentrated moral indictment of industrial modernity.

Critical angles: - The novel’s polemical style, use of caricature vs. empathy, and the role of imaginative art (Sleary) as humane alternative.

9. Wilkie Collins — The Woman in White (1859)

Synopsis & Form: A sensation novel told through multiple first-person narratives and documents (the epistolary/diary technique). Mystery, wrongful confinement, bigamy, and conspiracy drive the plot.

Themes & Significance:

- Pioneered detective and sensation fiction in Victorian England; explored legal vulnerabilities of women and anxieties about identity and inheritance.

Critical angles: - Gendered legal critique, narrative framing and suspense, and form as means of persuasion (multiple testimonies).

10. Oscar Wilde — The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890)

Synopsis & Form: A decadent novel examining aestheticism and moral corruption. Dorian Gray remains physically young while a portrait ages and reveals his moral degradation.

Themes & Significance:

- Interrogates “art for art’s sake” vs. moral responsibility; explores aesthetics, duplicity, and the late-Victorian anxieties about sexuality and decadence.

Critical angles: - Wilde’s paradoxical critique of aestheticism from within; the novel’s Gothic elements; late-Victorian fin-de-siècle culture.

VI. Themes, motifs, and critical concerns across the Victorian Age

1. Social Reform vs. Social Hypocrisy

Victorian literature often oscillates between moral earnestness (the belief in progress and reform) and exposure of hypocrisy — especially religious hypocrisy. Many novels present reformers and criminals in moral contrast; the social novel tries to diagnose and prescribe.

2. Gender, Domesticity, and the “Woman Question”

- Debates over women’s education, legal rights, and public roles appear in novels and essays.

- The “Angel in the House” ideal is both upheld and contested (e.g., Brontë, Eliot, Gaskell).

- Late-century feminists (Millicent Fawcett, Emmeline Pankhurst — political activism continues beyond 1901) are less literary but influence cultural debates; literary representations increasingly portray complex female subjectivity.

3. Science, Religion, and Doubt

- Darwinism complicates traditional religious cosmologies; poets and novelists negotiate faith and skepticism.

- Matthew Arnold, Tennyson, and Hardy each confront meaning in a scientific age, producing works of elegy and lament.

4. Empire, Race, and the Colonial Imaginary

- Imperial expansion produces adventure literature that simultaneously celebrates and questions empire.

- Late-Victorian writers increasingly depict colonized peoples in complex (sometimes troubling) ways; debates over “the white man’s burden” and missionary work appear in fiction and poetry.

5. Urban Experience and the City Novel

- The growth of London as a literary space is central (Dickens’s London is practically a character). Urban anonymity, slum life, and municipal bureaucracy are recurring topics.

6. Aestheticism and Decadence: Art for Art’s Sake

- Late-Victorian movements foreground art’s autonomy and the pursuit of beauty—often producing scandal and conservative backlash (e.g., Wilde’s trials in the 1890s).

7. Narrative Innovation and the Shape of Realism

- The century sees developments in point-of-view technique: free indirect discourse (Eliot), dramatic monologue (Browning), multi-voiced narratives, and documentary realism.

VII. Publishing, readership, and literary markets

1. Serialisation and the Periodical Press

- Many novels were first published in monthly or weekly parts (Dickens, Thackeray), shaping narrative pacing, cliff-hangers, and reader expectations.

- Magazines and reviews (e.g., Cornhill, Household Words, Macmillan’s Magazine, Reynolds’s, Punch) fostered public debate and critical taste.

2. Literacy and Reading Publics

- Elementary education expansion widened readership; middle-class readers in particular formed a strong market for novels, conduct literature, and periodicals.

3. Libraries and Circulation

- Lending libraries (e.g., Mudie’s Select Library) influenced what was read and the economics of book production; lending ensured repeated readership and word-of-mouth success.

VIII. Critical approaches and interpretive frameworks (for advanced study)

Victorian literature offers rich terrain for many critical methods:

- New Historicism / Cultural Materialism: Reading texts in relation to economic, political, and institutional forces (printing, reform legislation, imperial administration).

- Feminist and Gender Studies: Examining representations of women, domestic ideology, sexual double standards, and the intersection of gender with class and empire.

- Postcolonial Criticism: Interrogating imperial narratives, racial representation, and colonial ideology in adventure and travel literature (Kipling, Haggard).

- Ecocriticism: Investigating representations of rural change, industrial damage, and nature in Hardy, Gaskell, and Wordsworth’s later reception.

- Psychoanalytic and Trauma Studies: Reading Victorian anxieties about identity, repression, and sexuality (Wilde’s trials; Décadence; repressions in the family novel).

- Formal & Narratological Analysis: Close attention to serialization effects, narrative voice, and free indirect discourse in major realist novels.

IX. Legacy and transition to the twentieth century

Victorian literature’s complex legacy feeds directly into the early twentieth-century literary scene: modernist experimentation reacts to late-Victorian realism and aestheticism; the social novel’s concerns continue in 20th-century social fiction; and debates about gender, empire, and science evolve into modernist and postcolonial critiques. Figures such as Hardy and Conrad mark transitional authors who bridge Victorian narrative forms and modernist sensibility.

X. Annotated bibliography and recommended editions

Primary texts (recommended scholarly editions):

- Dickens, Bleak House (Penguin/Everyman/Oxford).

- Eliot, Middlemarch (Penguin/Norton Critical Edition).

- Tennyson, Poems (Cambridge/ Oxford /Norton).

- Browning, Selected Poems & The Ring and the Book (Penguin/Oxford).

- Hardy, Tess of the d’Urbervilles & Jude the Obscure (Penguin/Norton).

- Thackeray, Vanity Fair (Penguin/Everyman).

- Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray (Oxford World’s Classics).

- Kipling, Kim (Penguin/ Oxford).

- Gaskell, North and South (Oxford World’s Classics).

Secondary scholarship (introduction to advanced):

- A. N. Wilson, The Victorians (overview; readable).

- Terry Eagleton, The English Novel: An Introduction (contextual studies).

- Isobel Armstrong, Victorian Poetry: Poetry, Poetics and Politics (advanced).

- Michael Mason, The Making of Victorian Culture (historical-cultural background).

- Juliet John, Dickens and Mass Culture (print culture approach).

- Sandra M. Gilbert & Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic (feminist reading of the Victorian novel).

- Patrick Brantlinger, Rule of Darkness: British Literature and Imperialism, 1830–1914 (postcolonial approach).

XI. Syllabi, seminar suggestions, and exam questions (advanced)

Seminar clusters:

- Realism and the Social Problem Novel: Dickens (Bleak House), Gaskell (North and South), Hardy (Tess).

- Victorian Poetry and Science: Tennyson (In Memoriam), Arnold (Dover Beach), Darwin’s Origin as contextual partner.

- Gender and Domesticity: Brontë sisters (Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights), George Eliot (Middlemarch), feminist criticism.

- Empire and Adventure: Kipling (Kim), Haggard (She), travel narratives and missionary literature.

Sample exam questions:

- “Discuss how Dickens uses narrative perspective in Bleak House to critique Victorian legal institutions.” (essay)

- “Compare and contrast the representation of women’s moral agency in Jane Eyre and Middlemarch.” (comparative essay)

- “Explain how Darwinian thought shaped Victorian literary representations of nature and human identity.” (short answer + textual examples)

- “Close reading: Analyze the dramatic monologue ‘My Last Duchess’ as a critique of Victorian patriarchal authority.” (extract-based close reading)

XII. Conclusion

The Victorian Age is an era of contrasts — confidence and anxiety, expansion and restriction, reform and repression. Its literature is correspondingly diverse: it records the industrial metropolis, provincial life, the empire’s reach, interior psychology, and the late-century turn to aestheticism. Victorian writers grapple with ethical responsibilities, the meaning of progress, and the dilemmas posed by science and social change. For students and scholars, the era offers abundant materials for historical, formal, and theoretical exploration: the novel’s social conscience, the lyric’s theological questioning, and the late-century aesthetic experiment make the Victorian period a central field for higher literary study.